Hartlepool Sports & Leisure

Hartlepool Sports & Leisure

- Cinemas, Theatres & Dance Halls

- Musicians & Bands

- At the Seaside

- Parks & Gardens

- Caravans & Camping

- Sport

Hartlepool Transport

Hartlepool Transport

- Airfields & Aircraft

- Railways

- Buses & Commercial Vehicles

- Cars & Motorbikes

- The Ferry

- Horse drawn vehicles

A Potted History Of Hartlepool

A Potted History Of Hartlepool

- Unidentified images

- Sources of information

- Archaeology & Ancient History

- Local Government

- Printed Notices & Papers

- Aerial Photographs

- Events, Visitors & VIPs

Hartlepool Trade & Industry

Hartlepool Trade & Industry

- Trade Fairs

- Local businesses

- Iron & Steel

- Shops & Shopping

- Fishing industry

- Farming & Rural Landscape

- Pubs, Clubs & Hotels

Hartlepool Health & Education

Hartlepool Health & Education

- Schools & Colleges

- Hospitals & Workhouses

- Public Health & Utilities

- Ambulance Service

- Police Services

- Fire Services

Hartlepool People

Hartlepool People

Hartlepool Places

Hartlepool Places

Hartlepool at War

Hartlepool at War

Hartlepool Ships & Shipping

Hartlepool Ships & Shipping

Wreckmap Tees Bay 2004 Project Report

NAS NE / Tees Archaeology

Wreckmap Tees Bay 2004

Introduction

The Maritime component of the ‘Historic Environment Record’ (HER), for the area covered by Tees Archaeology, contains a high number of potential historic and archaeological sites requiring further investigation, surveying, recording and monitoring. It is fair to say that the majority of these sites are shipwrecks, many recorded as offshore casualties, but also a significant number of inter-tidal, or foreshore sites.

It was one such foreshore site that formed the core of the Wreck Map Tees Bay 2004 Project, which took place over five days at the beginning of August, 2004.

Historical and Archaeological Background

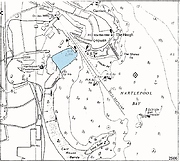

The gently shelving Middleton Sands (or more properly Middleton Strand – Image Gallery – Image 1), has long been used as a safe beaching ground for vessels unable to make either the Old or West Harbours through stress of weather. Certainly during the 19th and early 20th centuries, this characteristic and a number of locally-based ship repair/salvage companies, meant that the vast majority of stranded vessels were successfully refloated. However, such were the huge numbers of vessels involved, the small percentage that did become total wrecks comprised a significant number in their own right.

In recent years, Tees Archaeology staff and NAS NE Volunteers have carried out a small number of ‘rapid assessments’ on various chance maritime finds reported by members of the public.

Location

The project focused on the remains of a small wooden shipwreck (Image 2), lying on Middleton beach and was first reported in 2001 by members of the Hartlepool National Coastwatch organisation, whose building overlooks the wreck.

An initial site visit revealed little about the vessel, other than she was found to be lying parallel to the beach, a little below the half-tide line and was fastened together with wooden dowels, known as treenails.. No other information about the vessel was available, with its name, type and date of loss being unknown – truly a mystery ship.

Although usually completely buried, it is occasionally exposed through a combination of various tidal and weather conditions. The beach itself is enclosed between the traditionally separate and distinct medieval ‘Old Harbour’ to the north, and the Victorian ‘West Harbour’ to the south.

The beach surface comprises a thin layer of relatively fine sand, overlying a very stony layer of beach pebbles and demolition rubble, further evidence of which can be seen at the top of the beach; sea-coal, often in relatively deep layers, covers large areas of the sands after every tide, and forms an important local industry.

Aims and Objectives

Run as part of the NAS Training Programme, this excavation brought together a team of six NAS members from all over the country, most with very little practical maritime archaeological experience. Under the guidance of the three NAS NE Tutors, the project aims were very simple i.e. to:

- provide the NAS members with practical experience of working on a maritime site, sufficient to allow them to submit their work as a Part II project

- define the type, extent and condition of the vessel, and record as much of the structure as possible in the short tidal windows available

- draw reasonable conclusions based on the data obtained, as to the potential identity and/or history of the vessel

Putting into practice some of the techniques learned from the Introduction and Part 1 Courses, the team would gain valuable experience of the use of 2D Survey Methods (Triangulation, Trilateration, Datum Offsets), photographic recording and site plan drawing. Not least, practical site management skills would be learned, for example, in developing measures to ensure the site was adequately drained to allow recording to be carried out – not as easy as it sounded!

Methodology

The project was timed to coincide with a period of low Spring tides, thereby maximizing the on-site tidal window. This allowed a working period of some 5 hours per day, and the excavation team followed Tees Archaeology guidelines for best archaeological practice and Health & Safety requirements.

At the time of the project, the site was completely buried, and had to be re-located using transit marks taken during 2001 (Image 3). The excavation was wholly carried out by hand, and all trenches sand-bagged and ‘made safe’ at the end of each working day.

Observations and Results

Digging conditions were surprisingly difficult, with a substantial stony layer just below the surface sand. Keeping the excavation free of standing water was also a major problem, and a great deal of effort went into maintaining drainage channels (Image 4).

These conditions, and the lack of plant excavation machinery, prevented the full extent of the vessel being discovered. Nevertheless, over 30 individual frames, or ribs (Image 5), from either the port or starboard side of the vessel were identified and tagged, as well as a number of both inner (ceiling), and outer hull planks. Wooden treenails were almost exclusively used as fasteners; samples taken from the lower hull revealing hand-cut rather than machine-turned treenails.

The condition of the timbers was very good and the structure as a whole was seen to be holding together extremely well. The individual frames varied enormously in their dimensions: sidings (width), ranged from 3½ inches (90mm) to over 10 inches (250mm), and mouldings (depth or thickness), from 4½ inches (115mm) to over 7 inches (180mm). All were closely spaced producing a very strong craft.

With the presumed remainder of the vessel too deeply buried to be located or excavated, attention focused on an area of the hull that could be seen to be curving inward, towards what would be either the bow or the stern of the craft. Following a brief discussion amongst the excavation team, this area was designated to be the bows, with the visible frames therefore forming the port side of the vessel. A trench was then dug from the foremost frames in towards the centreline of the vessel in an effort to establish the presence of a keelson, however, despite strenuous efforts, the unstable nature of the ground and the depth of the excavation trench itself, prevented this being achieved (Image 6).

Small pieces of coal were found lying between the frames at the lowest point of the excavation; this coal still retained relatively sharp edges, clearly indicating it had remained undisturbed since first accumulating in this location. No other diagnostic material was found.

Postscript

In November 2005, winter storms succeeded in removing a great deal of beach material from the Strand, exposing much more of the vessel than had previously been seen before (Image 7). A rapid survey of the visible remains indicated the vessel was at least 17m long and had a minimum beam of some 6m. At least five ‘new’ ceiling planks were recorded, measuring either 8 or 9 inches in width (200 or 230mm), and 3 inches (75mm) thick. All noted fasteners, with the exception of one copper spike, were treenails.

Conclusions

The Project undoubtedly succeeded in its aim of providing NAS members with practical, ‘hands-on’ experience of what may be regarded as a typical small-scale excavation of a foreshore wreck. Indeed, this exercise fully illustrated the difficulties and time constraints likely to be encountered on similar foreshore excavations.

As a consequence of the difficult ground conditions, the depth at which the remains were lying and the lack of excavation machinery, the full extent of the wreck could not be established. Nevertheless, at the end of the excavation, the team all felt that a significant proportion of the vessel still survived more or less intact, a belief borne out by the beach loss event in November 2005.

Success in establishing the vessel’s name and history proved equally elusive, despite an excellent response from the public to an appeal in the press for information. However, much has been learnt about this ‘mystery’ vessel simply through piecing together all the archaeological clues and evidence. For example, the vessel is very strongly built, and with the presence of coal between the ceiling and outer planking, it would be reasonable to assume the vessel had served some time in the coal trade. From its position relatively high up the beach, in an area famed for its ship builders/repairers, it is highly likely that the vessel was heavily salvaged/dismantled once all possibility of refloating her had gone; a process that would certainly have seen all of the accessible masts, decking, frames, hull planking, and general stores, fixtures and fittings removed.

The Middleton Strand Wreck has proved to be an excellent training resource. With its relatively small size, intact structure and good location, it provides not only a challenging excavation, but also the potential to generate further ‘real’ archaeological and historical information, leading to a much enhanced maritime archaeological record…. and it was great fun!

Gary Green

NAS NE Regional Co-ordinator

2005

Related items :

Middleton Shipwrecks

Middleton Shipwrecks

There have been a large number of shipwrecks and strandings on the short stretch of sand between the West and Old Harbours at Hartlepool.

More detail » Nautical Archaeology Society North-East

Nautical Archaeology Society North-East

The Nautical Archaeology Society North-East (NAS NE), is a regional branch of the Nautical Archaeology Society (Registered Charity No.264209), run by a small number of Volunteers. Over the years, NAS NE has developed strong working links with a number of regional organisations, in particular Hartlepool Borough Council’s Library and Museum Services, Tees Archaeology, English Heritage and a wide range of local Groups and Societies.

As a result of these partnerships, NAS NE has been able to run some very successful community-based grant-funded projects, encouraging people of all ages to take an active role in researching and recording our region’s rich maritime heritage. This section of the website contains a selection of these projects.

More detail » Wreckmap Tees Bay 2004 Report Images

Wreckmap Tees Bay 2004 Report Images

The images in this gallery relate to the 'Wreckmap 2004' Project Report.

More detail »