Hartlepool Sports & Leisure

Hartlepool Sports & Leisure

- Cinemas, Theatres & Dance Halls

- Musicians & Bands

- At the Seaside

- Parks & Gardens

- Caravans & Camping

- Sport

Hartlepool Transport

Hartlepool Transport

- Airfields & Aircraft

- Railways

- Buses & Commercial Vehicles

- Cars & Motorbikes

- The Ferry

- Horse drawn vehicles

A Potted History Of Hartlepool

A Potted History Of Hartlepool

- Unidentified images

- Sources of information

- Archaeology & Ancient History

- Local Government

- Printed Notices & Papers

- Aerial Photographs

- Events, Visitors & VIPs

Hartlepool Trade & Industry

Hartlepool Trade & Industry

- Trade Fairs

- Local businesses

- Iron & Steel

- Shops & Shopping

- Fishing industry

- Farming & Rural Landscape

- Pubs, Clubs & Hotels

Hartlepool Health & Education

Hartlepool Health & Education

- Schools & Colleges

- Hospitals & Workhouses

- Public Health & Utilities

- Ambulance Service

- Police Services

- Fire Services

Hartlepool People

Hartlepool People

Hartlepool Places

Hartlepool Places

Hartlepool at War

Hartlepool at War

Hartlepool Ships & Shipping

Hartlepool Ships & Shipping

Wilson Family Album

Details about Wilson Family Album

A selection of photographs and documents kindly shared with this project by Mr. Stuart James Wilson.

Location

Related items () :

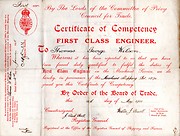

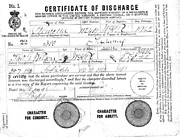

1st Class Certificate of Competency (front)

1st Class Certificate of Competency (front)

Created by Board of Trade

Donated by Stuart James Wilson

Created by Board of Trade

Donated by Stuart James WilsonDated 1917

Belonging to Thomas George Wilson and reissued as a result of the sinking of the steamer Foylemore by U-boat.

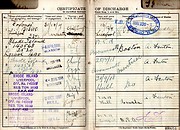

More detail » 1st Class Certificate of Competency (reverse)

1st Class Certificate of Competency (reverse)

Created by Board of Trade

Donated by Stuart James Wilson

Created by Board of Trade

Donated by Stuart James WilsonDated 1917

Belonging to Thomas George Wilson and reissued as a result of the sinking of the steamer Foylemore during the Great War.

More detail » Biographies of James and Elizabeth Wilson

Biographies of James and Elizabeth Wilson

JAMES AND HANNAH MARY ELIZABETH WILSON (NEE HEATLEY)

James Wilson, second son of Thomas George Wilson and his wife Ada, was born on St. George’s Day, 23rd April, 1898 at 14 Mary Street. He was a pupil at Church Square School and badly wanted to go to sea like his father. Unfortunately, his ambition was stymied by his headmaster, Mr. S. S. (“Gaffer”) Gunn, who advised Ada Wilson that her son was “far too clever for that” (!) and should be put to work in a commercial office at the earliest opportunity.

James began work as an articled clerk at Fortune’s accountancy practice in Church Street, where his youngest brother, Eric Wilson, would also work. He was trained in book-keeping, typing and Pitman’s shorthand, also receiving private tuition paid for by his parents. James was also highly skilled in calligraphy, writing in “copperplate.” At some point prior to the autumn of 1924 he changed employers, working first as a time-keeper and then as a clerk for the South Durham Steel & Iron Co. at what became known as their North Works.

Like his maternal uncle, Edgar Coates, Jim was a gifted, if self-taught linguist. He became fluent in several languages, including Esperanto, and especially French – even to the distinction between the refined Parisian and harsher Marseilles accent. In fact, he often worked as a translator at the steelworks, processing foreign orders or enquiries and giving foreign VIP’s a guided tour of the works. In his politics James was an International Socialist, rabidly so, and also – in spite of having been brought up in the fold of the Wilson family’s Primitive Methodism – an atheist.

In addition he enjoyed natural history, botany, mathematics and geography. His son, Jim Wilson, remarked that upon returning from foreign climes as an engineer-officer in the Merchant Navy, his father knew more about the places he’d been too than he did . . . and he’d been there! James was also fascinated by the North American Plains Indians and by the history of the Zulu nation in their struggles against the Boers and the British. In addition, he followed minority sports such as speed-skating and bicycle pursuit racing. His great heroes were Cecil Rhodes, founder of Rhodesia, and Sir Clowdisley Shovell (who rose from cabin boy to Admiral only to be drowned when most of his squadron was wrecked due to navigational error in 1707).

Whilst most of his pursuits were intellectual, James could also be very practical, building his own kayak and growing a range of vegetables, fruits and flowers. He was also a great one for walking. During the bombardment he walked to Spennymoor to join the rest of the family, then staying with a relative. He often hiked to Dalton-on-Tees, where his parents had a summerhouse.

During the Great War he witnessed the destruction of Zeppelin L.34, shot down in Tees Bay, and remembered how the streets were thronged with onlookers, gazing up into the night sky. He was conscripted as a result in the 1916 “call up,” but rejected on medical grounds. However, massive casualties forced a rethink and he was taken into the army, where his skill with a rifle earned him a recommendation for sniping duties. Thankfully, the war ended before his training was complete. Consequently, he hiked home to West Hartlepool from the army depot at Seaham Harbour. During the Second War James was a volunteer fire-watcher at his workplace and a member of the 18th (Durham) Infantry battalion, Home Guard.

Taught to sail by a boat-owning friend, a great passion was to hire a fishing coble from Middleton and sail down the coast on weekend trips. His niece, Maureen Jones (nee Wilson), described him as “a glamorous eccentric.” His eccentricity extended to teaching himself to swim, practising his strokes while stretched out on a kitchen stool!

James Wilson married Hannah Elizabeth Heatley of Stockton-on-Tees at Stockton’s parish church on 18 September 1924. Born on 21 November 1905, Elizabeth was the daughter of a shipyard foreman. Her nickname was “Topsy,” after the fictional children’s character. A former pupil of Stockton’s High School, she met James through her newly married sister, Iris Ivy, and her husband, who moved to the Hartlepools and knew James’s younger brothers, Edgar and Stan.

James and Elizabeth Wilson lived at the following addresses:

- Penzance Street, briefly, when first married.

- 25 Ladysmith Street, a two-up, two-down street-house on the edge of the Longhill estate.

- 7 Elcho Street, where James built his kayak.

- 9 Henderson Grove, a semi-detached “council house” backing onto the Victoria Ground and looking onto the “Queen’s Rink” dancehall.

- 114 Raby Road – another council “semi” this house was built shortly after the Second World War.

Latterly, the couple moved in with their youngest daughter.

James and “Topsy” had four children, two boys and two girls. The eldest boy was Jim Wilson, a biography of whom appears separately.

When war came Topsy was adamant that her children should not be evacuated. “If we go,” she said, “We all go together.” Like so many others, the Wilsons had a standard-issue corrugated-iron Anderson shelter dug into their back garden. A gap in the iron sheeting enabled those taking refuge to keep track of proceedings in the night sky. With regard the night-time air-raids Jim Wilson remembered the throbbing drone that announced the arrival of German bombers overhead and of the long fingers of light probing skywards across the clouds in their quest to illuminate the enemy. If caught in a searchlight beam, the enemy aircraft would appear ghostly and moth-like. With a target to shoot at, the darkness would be punctuated by bursts of anti-aircraft fire whilst tracer bullets would be seen to float up from warships in the docks. He described the crump and chatter of the guns, the banshee whistle of falling bombs and the earth-shaking noise of an explosion. This last, he said, was “like the crack of bloody doom.”

James and Topsy’s children all had narrow escapes during the war:

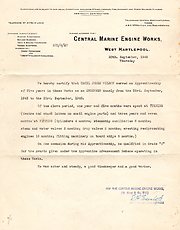

- In the early raids nothing could persuade June Wilson to go into the shelter. She preferred to stay in the house, occupying a cupboard under the stairs. During one raid a badly fused anti-aircraft shell exploded over the Wilsons’ house, blowing out windows and cracking walls. After that, June joined the rest inside the shelter! June worked a shaping machine operator at the Central Marine Engine Works during the war under the direction of Miss Winnie Sivewright, J.P., the daughter of a local naval architect. June looked back at her war-work with pride and affection. Hers was a wartime marriage, to William Fawley, who was stationed at West Hartlepool and served as a radar operator in the RAF. The couple married at Christ Church on September 14th, 1943.

- On his way home from study at night-school, Jim Wilson was astounded to find the pitch-blackness suddenly transformed by the intense, eerie light of a sputtering parachute flare used by bombers for “spotting” their targets. No siren had sounded and the flare lit up a huge area, with Jim right in the middle of it. Said Jim: “I’ve never felt so naked!”

James Wilson himself had a very lucky escape. Walking home from fire-watching duty in the early hours of August 27th 1940, James and a fellow member of the works’ office staff were caught up in a German air raid as they walked along Church Street. They discussed whether to shelter in the doorway of the Yorkshire Penny Bank but decided to press on. Shortly afterwards, at 12.50 am, the properties adjoining the bank took a direct hit from bombs intended for the railway and were completely destroyed. The bank itself was so badly damaged that it had to be demolished.

James Wilson retired from clerking at the steelworks in 1963. Towards the end of his life he suffered from ill health, including glaucoma and cataracts that left him blind in one eye and partially sighted in the other. He died of pneumonia, after a stroke paralysed his vocal chords and deprived him of his beloved linguistic abilities, in Hartlepool General Hospital on December 21st, 1969. His body was cremated and the ashes were scattered in the Garden of Remembrance at Stranton Grange Cemetery. In terms of character and personality James Wilson was a stoic, but his son-in-law Bill Fawley said of him that: “He never said a bad word about anyone, and if he could help with anything, he would.” Elizabeth Wilson also passed away at home, on Lady Day (March 25th) 1974.

Source: “The Wilsons of Whitby and West Hartlepool,” Vol. 5. See also images.

More detail »

Biographies of Joseph and Mary Jane Almond

Biographies of Joseph and Mary Jane Almond

JOSEPH ALMOND AND MARY JANE (NEE SIDNEY): HISTORY AND FAMILY

Joseph Almond was born at Sunderland on June 9th 1854, the son of Amos Almond, a forgeman, and his wife Frances (nee Ross). Joseph married Mary Jane Sidney (born April 1859) and by 1881 the couple were living at 32 Crescent Row, Sunderland. Both the Almonds and the Sidneys were long-established Wearside families. Joseph was a foregeman, though he also dabbled in boxing promotion. Around 1893/4 the Almonds moved first to Stockton-on-Tees and thence to West Hartlepool, arriving in the latter c. 1896. The couple had twelve children, three boys and nine girls, three of which, a girl and two boys, died in infancy. The surviving children of Joseph and Mary Jane were as follows:

Joseph Sidney Almond (born 3rd March 1877)

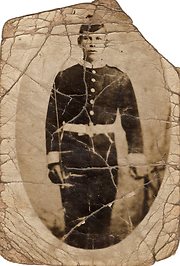

A forgeman by trade, like his father, he joined the 3rd (Militia) Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry, seeing active service in the Boer War. The 3rd Durhams were attached to the regular 1st Btn, and also performed the wearisome duty of guarding the Natal Railway. This involved the occupation of specially built blockhouses with a view to the protection of transport and communications.

Pte J. Almond, 3rd DLI, posted a letter home to his mother, then living at No. 3 Dorset Street, West Hartlepool, which was published in the “Northern Daily Mail” on the 21st of July, 1900 (p4c6). It was written at Springfontein and reads as follows:

“The majority of people at home think that England has nothing to do but walk in and take this rich colony, but, believe me, if they saw the country they would say it was an impossibility for any three nations, or even the world combined, to take it. It is nothing but a mass of hills and kopjes. To my idea, the Boers should never have been driven back from the splendid fortifications that they held, or, indeed, ever shifted from them. Had England been in the place of the Boers she could safely have defied the world. There are an awful lot of deaths out here, chiefly from dysentery, black fever, enteric fever, &c. These are very severe complaints, and only one in ten gets over them. We are fairly up to the front, but so far we have been in no engagement. I think it was a most disgraceful shame the way that the 3rd Durhams were treated. We were not dressed in khaki until we had been out here three months, and under a scorching sun, it was very severe on us. They are now trying to make a mounted infantry corps from us. They asked for and obtained 50 volunteers for that purpose. There are so many false rumours that are going about that you cannot believe anything that is said. In the first place, we were to be on our way home on the 15th of this month. Now it has to on August 18, but no sooner than this was rumoured than we got orders for 20 men and a sergeant to go higher up country, so that I believe nothing. All the time I think the day for our return will come very suddenly and unexpectedly – and may it be soon!”

Private J. S. Almond (No. 3026) received the Queen’s South Africa Medal for his soldiering in the Boer War. In addition, the “Northern Daily Mail” of 4th July 1901 recognises the name of J. Almond, 3rd DLI as amongst “Our Local Warriors - The Proposed Public Welcome” concerning public recognition of troops.

Known as “Joss,” Joseph Sidney Almond married Margaret Ann Warvill, daughter of Benjamin and Ann (nee Smiles) at West Hartlepool on October 17th 1907. The couple had six children, three of which were boys. The eldest was Joseph Sidney Almond jnr, born 17 February 1908. He became a shopkeeper with premises in Russell Street. Known to most as Sidney but to some as Joe, he married a Mormon girl in April 1933 and the couple later moved to Salt Lake City, Utah, USA. Their daughter, June, and her husband David Jeppson, currently live in Toqueville, Utah, where David is a prominent member of the church and a respected community figure. Joseph Sidney Almond jnr passed away on October 29th 1984.

“Joss” Almond died on the 1st of June 1930. His widow, who moved to Pease Street, passed away at West Hartlepool on September 29th, 1963.

Edmund Hepple Almond (born 9th April 1880)

Edmund was named in honour of a relative, Edmund Hepple Almond of 9 Crescent Row, Sunderland, who died age 26 years and was laid to rest at Bishopwearmouth on October 22nd 1871. The Hepple surname is known to be connected with pit-sinking, as was that of Almond. Edmund’s paternal grandfather was Joseph Almond. A pit-sinker, he appears to have worked on the sinking of the Monkwearmouth shaft, then the deepest in the world. Joseph was the husband of Isabella (nee Sadler) and the couple were married at Monkwearmouth on September 18th, 1831.

Edmund Hepple Almond, second son of Joseph Almond and Mary Jane (nee Sidney) married Margaret Haydon, daughter of Robert and Eliza (nee Greethead) on 12 July 1898 at Stockton register office. Edmund was then an ironworks labourer and both bride and groom gave their address as 9 Seaham Street, Stockton-on-Tees.

By 1901 Edmund and family were living at 19 Gas Street, West Hartlepool, with Edmund as a forge labourer. In 1911 the family could be found at 45 Garrick Street, South Shields, and Edmund was by then an electric tramway ticket inspector. His wife Margaret passed away in July 1958 at South Shields, but Edmund emigrated to Australia, living in central Melbourne. He died there on March 19th, 1968. During the Second War Edmund was visited by his nephew, Kenneth Ross whilst Ken was serving as a Seaman Gunner aboard HMS “Swiftsure,” then operating with the British Pacific Fleet.

Edmund Hepple Almond and Margaret Haydon had seven children:

- Henry Bright Almond (1899-1986)

- Elizabeth Hannah Marian Almond, later Mrs Leadley (1901-1985)

- Edmund Almond (1902-1991)

- Robert Amos Almond (1904-1992), who passed away in Victoria, Australia

- Gertrude Rose Wingfield Almond (1907-2001), later Mrs McLauchlan, she died in Toronto, Ontario, Canada

- Sydney Almond (1912-2007)

- Joseph Almond (1913, born prematurely as the result of a fall, he lived for only one day)

Elizabeth Ann Almond ((born 23rd October 1881)

Her husband, John Henry (“Jack”) Birkbeck, was a coalman for Laytons of West Hartlepool. He fought on the Western Front during the Great War and was invalided home with pneumonia. In 1894 Jack’s father, Henry Birkbeck, a resident of Gloucester Street, West Hartlepool, helped to install the boilers at George Weddell’s Cerebos Salt works at Greatham and was later blinded in an industrial accident, apparently the victim of boiler-furnace “blow-back.”

Jack and Elizabeth Ann (nee Almond), of Eton Street, West Hartlepool, had six children:

Joseph Wilfrid (Wilfie): A capable man, he served as a pre-war regular soldier with the DLI and as a member of the “Desert Rats” during the Second World War, with the 16 Btn DLI. Wilfie was killed at the village of Sedjenane, Tunisia, on March 2nd 1943. This action took place following the German counter-attack after the British victory at El Alamein and the consequent “Operation Supercharge” in which the Durhams played a major role. His name is inscribed on a memorial plaque in West Hartlepool’s Victory Square.

Rudolf: Served in the army during World War II, being stationed in the UK .

John: saw action in World War II with the DLI at Dunkirk. He was then sent to the Far East and was taken prisoner by the Japanese, being one of those who worked on the infamous Burma Railway. He survived the ordeal, married and had three sons.

Thomas (Tommy): Like his brother Rudolf he too served in the army during WWII and was stationed in Britain. Neither Rudolf nor Tommy ever married.

Lily: She married William Simpson (Bill) Jervis (born Birslem, Stoke-on-Trent). Bill Jervis became a distinguished servant of West Hartlepool. A Labour Councillor for the Brinkburn Ward, he was also an Alderman of the town, a Justice of the Peace and Northern Regional Chairman of the MENCAP Charity. Bill and Lil had four children – Lily (who became an Assistant Manager with Hartlepool Social Services), Gloria (married to John Featherstone, a shipwright, the couple lived at Billingham), Sybil, who was born with Downs Syndrome and became the inspiration for Bill and Lil’s tireless charitable work, and William Frank Ellis Jervis. Bill, as he is known, served his apprenticeship with Richardsons, Westgarth engine works (Hartlepool) and became a planning engineer, working on oil rigs and nuclear power stations.

Minnie: Lived in West Hartlepool all her life and, like Rudolf and Tommy, never married.

Frances Anna Almond (born 23 January 1883)

Frances emigrated from West Hartlepool to Canada after the Great War, with her husband, Charles Scott. She died in 1964.

Lavinia Almond (born 12 January 1885)

Lavinia and her husband, Alex Watt, also emigrated to Canada. The couple had three children. Biographical information on Lavinia and her family can be found attached to her photograph.

Mary Jane Almond (born 25 November 1887)

Her first husband, Thomas Patterson Stenton, was killed in action during the Great War and his name appears on the War Memorial in Hartlepool’s Victory Square. Mary Jane and Thomas had one son, but he died in infancy – a victim of the Spanish ‘Flu epidemic. Mary Jane remarried and her second husband, Joe Richards (born South Shields) had also served during the Great War, in the Royal Engineers. He was a fierce atheist – unsurprisingly so, as during combat he’d been spattered with his mate’s brains. Joe’s father was a founder-member of Mineworkers’ Union and was blacklisted for many years as a result. His grandfather was reputed to have been a rather less laudable character. Chippendale Richards was a confidence trickster who made his living by touring the country with a female accomplice and posing as a photographer. After pretending to take photographs he’d disappear into the night with the takings!

Mary Jane and Joe Richards moved to Shields, where they had two sons, Joseph and John, before moving down to Dulwich, London. Both Richards boys served in the army during WWII and Joseph married an Italian girl, Giorgia Seccia. John became a civil servant and was also a member of Mensa. Mary Jane Richards (formerly Stenton nee Almond) died after a short illness in 1963.

Annie Almond (born June 1889)

Annie married twice, once to John Barker and then to Mr. N. Fortune of West Hartlepool. Annie Fortune (nee Almond) of Welldeck Road, West Hartlepool, is known to have had three children.

Sophia Almond (born 1891)

Died in infancy.

Isabella Almond (born 15th October 1892)

Isabella’s biography is given elsewhere, together with that of her husband, Walter Malcolm Ross.

Minnie Almond (born 31st March 1894)

Minnie was the only one of the Almond children to have born at Stockton-on-Tees. All of her previous siblings were born at Sunderland. Minnie and her husband, Pickering Calvert, a baker, moved from their home at 25 Park Street, West Hartlepool, to live in the town’s Leamington Drive. The couple had three children, two girls (Muriel and Vera), and a boy (John). The family later moved to Bridlington on the North Yorkshire coast.

Joseph and Mary Jane Almond’s remaining two children were born at West Hartlepool. The first, a son named Amos, was born on August 12th 1897 and died on the 9th of August 1898. Another boy was born to them in 1898 and also died in infancy.

Mary Jane Almond, a resident of 32 Richard Street, West Hartlepool, passed away in February 1939. Her husband Joseph died the following month.

Source: “The Ross Family and Others” by Stuart James Wilson

More detail »

Biographies of Walter and Isabella Ross (nee Almond)

Biographies of Walter and Isabella Ross (nee Almond)

WALTER MALCOM ROSS (A.K.A. GOODMAN) AND ISABELLA (NEE ALMOND)

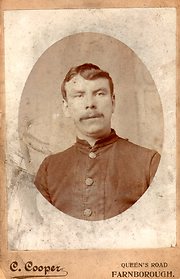

Walter Malcolm Ross was born at 84 Ravenspurn Street, Grimsby, on the 18th of November, 1891. He was the youngest child and only surviving son of Henry Malcolm Montague Ross and his wife Hannah Rebecca (“Annie”) Ross (nee Rack). Henry, known as “Harry,” was a Scot and had been born at Glasgow. He sailed as a mate on Grimsby fishing smacks. Annie came from a long-established Lincolnshire family. Henry and Annie’s marriage broke up and Annie took her children to Birmingham, where her brother had settled. Henry remained at Grimsby, also sailing as an Able Seaman aboard tramp steamers. He died in hospital of a head injury, apparently sustained at sea, in 1900.

Walter Malcolm Ross grew up in Aston, Birmingham, where he lived with his mother, step-father (William Goodman) and his younger half-brothers, William and James. On leaving school, he took work as a French Polisher. It seems, however, that Walter, a lad of good character, wished to see a little more of the world, so – under the name of Goodman – he enlisted in the British Army at Birmingham on June 23rd, 1910. He was then living at 125 Park Lane, Aston.

Walter expressed a preference for the Durham Light Infantry. Why this was remains a mystery, especially in view of the Cardwell reforms of 1881 that introduced county regiments. Initially, Walter was posted to the 2nd Battalion DLI stationed at Fermoy in Ireland and thence to the depot at Colchester (Hyderabad Barracks). Upon transfer to the 1st Btn he sailed from Southampton via troopship, the steamer “Hardinge,” for India on October 29th, 1912, arriving at Karachi on the 19th of November.

Private “Goodman” was stationed on the North West Frontier (NWF), guarding the Khyber Pass against invasion from Russia or neighbouring Afghanistan and also effecting the provision of internal security in a notoriously volatile area. His service on the NWF took him to Nowshera, Peshawar, Rawalpindi and Kuldana, patrolling the border country. India, with its snake-charmers and fakirs must have seemed a very exotic place indeed to any working-class young Briton.

Walter became a junior NCO. His service record shows that he accepted temporary promotions but declined them on a permanent basis, meaning that he wasn’t comfortable with the extra responsibility. He saw active service during the Third Afghan War that lasted through May and June 1919. April of that year saw the infamous “Amritsar Massacre” and the newly incumbent Amir of Afghanistan took advantage of the prevailing Anglophobia. His forces crossed the border into the Punjab, occupying a small village. The British responded with a rapid deployment facilitated by motor vehicles and good field intelligence, commencing full hostilities against the Afghans.

Most of the action comprised small-scale but quite vicious engagements and the British quickly secured a military victory. Walter Malcolm Goodman (Ross) saw active service at Landi Kotal. British and Indian battle casualties comprised 236 killed and 615 wounded. An outbreak of cholera killed a further 566. Walter’s Indian service came to end after this conflict. His character was described as “exemplary.” Demobilisation saw him sail home abord the P & O steamer “Khyber,” embarking at Bombay. He subsequently saw out the rest of his army career in the reserve, stationed at Newcastle and Ponteland. He received the following campaign medals: India General Service Medal with “Afghanistan” bar; 1914-15 Star; 1914-18 war Medal; 1914-18 Victory Medal.

On leaving the army in June 1921 Walter Malcolm Ross (aka Goodman) arrived in West Hartlepool, presumably as a result of the work opportunities there. Working as a shipyard labourer, he took lodgings at 50 Elwick Road (actually 51a, above a grocer’s shop), 42 Eden Street and then at 25 Park Street. The latter was the home of one Pickering Calvert, a baker. Calvert was married to Minnie, nee Almond, who had an unmarried younger sister, Isabella.

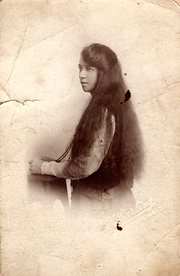

Daughter of Joseph Almond and Mary Jane (nee Sidney), Isabella Almond lived at 32 Richard Street. She’d been born at Sunderland on October 15th, 1892 and moved to West Hartlepool with her parents and siblings in the mid-1890s. A trained seamstress, Isabella first worked as a nursery maid at Tunstall Grange, West Hartlepool. This was the home of Sir Stephen Wilson Furness, a barrister and Liberal MP for the Hartlepools. During the Great War Isabella worked at the Hartlepools National Shell Factory, based at the Central Marine Engine Works of Wm. Gray’s shipyard. This employed 85 men and 365 women on the production of 8-inch High Explosive Shells. Isabella’s supervisor was the redoubtable Miss Winnie Sivewright, daughter of a local naval architect. Isabella’s photograph appears on Page 37 of George Colley’s “A Hartlepool Portrait” (1995), along with Miss Sivewright and selected members of the shell factory workforce.

Walter Malcolm Ross (aka Goodman) married Isabella Almond on the 12th November 1921 at West Hartlepool Register Office. Both the Ross and Goodman surnames attest on his marriage certificate. Shortly after his marriage Walter took his new bride to Grimsby, where the Goodmans were then living. He then learnt that his mother Annie, of 130 Burgess Street, Grimsby, had passed away. Walter Malcolm and Isabella Ross lived in a “two-up, two-down” at 21 Penzance Street, West Hartlepool, and had three children: Walter Edmund (born 27 August 1922), Kenneth Charles (born 13 May 1924) and Catherine Isabel (born 29 December 1929).

Sadly, Walter became very ill, having contracted tuberculosis during his army service in India. He took a job as commissionaire at the Northern Picture House but his physical condition declined, resulting in him becoming a permanent invalid. Isabella turned increasingly towards religion for emotional support. She attended meetings of the Seventh Day Adventists, being introduced by a friend, Mrs McMurdo of Studley Road, and was also a member of the Panacea Society, formed in memory of the so-called “prophetess,” Joanna Southcott.

In 1937 the Ross family were re-housed, moving to the modern, semi-detached 31 Wordsworth Avenue on the Rift House Estate. After a short time at a sanatorium Walter Malcolm Ross died at home of TB on December 28th, 1939 – the eve of his daughter’s 10th birthday and the 39th anniversary of his own father’s passing. The year of 1939 was a personally heartbreaking one for his widow. She lost not only her husband, but also both of her parents. Isabella’s two sons saw active service in the Royal Navy during the Second World War and the Hartlepools became a target for the Luftwaffe.

By the mid-1960s Isabella was in poor health and in the spring of 1966 she moved from her council-house in Wordsworth Avenue to Hazelhurst, an old-folks’ home in Wooler Road. She still made regular visits to see her daughter, Cathie Wilson (nee Ross) at the Wilsons’ home in Fenton Road but developed Alzheimer’s Disease, subsequently transferring to a specialised hostel at Throston Grange. She passed away at Hartlepool General Hospital on the 24th of November, 1972 and was laid to rest with her husband. Remaining possessions included her handbag. It contained nothing but her husband’s medals, a photograph of her youngest son, Kenneth, and a photo of her grandson, Stuart James Wilson.

Source: “The Ross Family and Others” by Stuart James Wilson.

More detail »

Biography of Ada Stebbings (nee Wilson)

Biography of Ada Stebbings (nee Wilson)

Ada Wilson

Born on 29 November 1900, Ada was the second daughter of Thomas George and Ada Wilson (nee Coates). In 1984, Ada left an account of her early years, including her memories of the Bombardment of the Hartlepools and a Zeppelin raid. Excerpts are as follows:

“One morning rather early in December 1914 having just left school and being one of a large family, 4 brothers and one sister and my mother pregnant, we were awakened by loud noises which we found out was gun fire being fired at us from a ship at sea. The family went downstairs where my mother got us all to hide under a heavy table in the dining room. We were very lucky as a lady living 2 doors away went out to the gate and was hit in the face by shrapnel. There was a scare that we were to be bombarded again on the Friday so all the family went to Spennymoor to a relative and we slept where we could.”

Ada continues:

“We soon came home and I got work in a small boot and shoe shop. As I wished to better myself I left after a few months and applied for work in a stockbroker’s office. I started there on Jan. 2nd 1916 and was employed until 1921 when with one or two other female colleagues our services were terminated due to the return of men from the war. While we were working we were asked to visit relatives of men killed in the war for particulars . . . and we compiled a list which with our names was buried in the War Memorial while it was being erected.”

She also writes that:

“I have a postcard of damage done to houses in Hartlepool. . . . I was taught typewriting in the office but went to evening classes for shorthand. One night a zeppelin was sighted. I don’t know if we were bombed but I remember running home, about a mile, in panic. My father, who was a Chief Engineer in the Merchant Navy, was at sea all during the war. . . .”

Ada then describes how her father survived two sinkings by U-boat and how he narrowly escaped internment at Bremerhaven upon the outbreak of hostilities, mentioning her brother Tom’s enlistment. The stockbroker’s where Ada worked was S. T. Coulson’s in Church Street. Upon leaving his employ she worked at the local labour exchange, being appointed union representative. Ada’s friend was May Bowden, who later married a shipping magnate and had the honour of launching a ship.

Ada Wilson married George Stebbings, an electrician. He was the son of Charles Stebbings, Head Gardener to Lt. Col. Wm. Thomlinson of The Green, Seaton Carew. Thomlinson was managing director of the local blast furnaces. In later life Colonel Thomlinson sat for a portrait, now in the collection of Hartlepool’s Museum Service. It was Charles Stebbings’ proud boast that he’d grown the flower shown in his employer’s buttonhole! His wife, Isabella, had once been maid to the Dowager Lady Oswald. A very prim and proper Highland Scot, she was rather taken aback by the relatively easy-going manners of the Wilson family! Charles and Isabella lived in a tithe-cottage at 10 Station Lane. Both are buried in Holy Trinity churchyard, Seaton Carew.

After her marriage Ada converted from the Wilsons’ Primitive Methodism to her husband’s Scottish Presbyterian faith. Owing to mass unemployment in the Northeast the couple also moved away to Leeds, where Polly Proudfoot, one of Ada’s aunts kept a lodging house and her clientele was composed of Anglican clerics. At Leeds, George Stebbings found work with a firm of insulation engineers, rising to become weaving manager. He died of an asbestos-related disease age 48.

By the time of George’s passing he and Ada were divorced. The couple had one child, Dorothy, who went to school in Glasgow and Lancaster. She trained as a nurse, later retraining to become a secondary school teacher (English and French). Dorothy and her husband Douglas, a production engineer, had two daughters. Both are graduates (business and languages respectively).

Ada Stebbings (nee Wilson) passed away in a Leeds nursing home in 1997. Her faculties remained intact to the end and she was able to recognise her nephew, Jim Wilson, during his television appearance as Project Engineer on the restoration of Britain’s first battleship, H.M.S. “Warrior” (1860).

Ada Wilson is remembered as an unorthodox and intelligent woman. A keen cyclist she was an early vegetarian and, like many of the Wilsons, a decent artist.

Source: “The Wilsons of Whitby and West Hartlepool,” Vol. 4 by Stuart James Wilson. See images.

More detail » Biography of Cathie Wilson (nee Ross)

Biography of Cathie Wilson (nee Ross)

CATHERINE ISABEL ROSS

Cathie Ross was born at 21 Penzance Street, West Hartlepool, the third child and only daughter of Walter Malcolm Ross and his wife Isabella (nee Almond) on the 29th of December, 1929. Owing to her father’s tuberculosis, contracted whilst serving with the army in India, the family knew considerable hardship and Cathie grew up to be a charity scheme away from being a bare-foot kid. Parcels were received from Cathie’s aunts in Canada, usually containing clothes, and these were very welcome.

Cath first attended Avenue Road School (headmistress Miss Colewray?) and remembers how, as a pre-school infant, she would sit in the back-street on a small wooden chair made by her father, there to watch the older children coming out of school. On her first day the children were given a small strip of leather with holes punched into it and with this they learnt how to tie shoelaces.

Cathie has written that he house in Penzance Street consisted of “a living room and kitchen and a back yard (in which was kept a zinc bath), containing a toilet and coal house. My father slept in one bedroom (because of his illness), my mother and I, plus my two brothers slept in one bed in the other bedroom, mother and I at one end of the bed, and my two brothers at the other end.

“A lot of people in those days believed that TB ran in the family (my mother did not), but this was because they did not know how infectious it was and my mother realised this and was very particular – keeping all his things separate, including his clothing, his washing and his crockery etc. As my brothers and I got older we were allocated a three bedroom council house, with living room, kitchen (containing coal house and pantry), separate toilet next to the back door and a bathroom, with front and back gardens. I was then 7 years of age. . . .” This was 31 Wordsworth Avenue.

Cath’s next school was St. Aidan’s, where the headmistress was Miss Mary Baty, who dressed in “widow’s weeds” (black) having been engaged to marry Mr. Theo Jones, a fellow teacher but also the first British soldier to have been killed on home soil during the Great War, a victim of the Bombardment of the Hartlepools in December 1914.

Upon leaving St. Aidan’s, Cathie attended Elwick Road School, passing “half-way” for her scholarship. In consequence she went to the Commercial Day School, situated on the top floor of the old Technical College in Lauder Street. There she gained RSA qualifications in English, Typewriting and Shorthand and Pitman’s theory and speed certificates, also in shorthand. Cathie had great praise for this progressive school and admitted that she “didn’t want to leave!” A great reader in her youth, her favourite author was Henry Rider Haggard and Cathie particularly enjoyed his “She” trilogy.

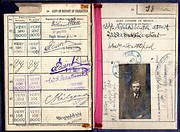

On leaving school she worked (briefly) as a shorthand typist at an accountancy practice in Church Street, at the Regent Travel and Traffic Bureau in York Road and for the Hartlepools Co-operative Society Ltd, Education Department, in Victoria Road. In 1948 she joined the Womens’ Royal Army Corps. After basic training with No. 3 Platoon, 3 Company, Auxiliary Territorial Service Training Centre, Cathie was posted to the 26th Independent Company stationed in barracks at Bushey Heath, Herefordshire.

Cathie served as a clerk-typist with No. 3 Platoon, later working as a stenographer on the compilation of a signals manual in co-operation with RAF Stanmore (Fighter Command). She was also based at Gresford in North Wales and served as a courier, transporting “Top secret” documents to Edinburgh Castle. Cath travelled by train in company with armed Military Policemen. Private C. I. Ross (Service No. W/353665) left the army on termination of her enlistment after serving a year and 348 days with “the Colours.” She was recommended for promotion but, like her father, didn’t want to accept it, and also turned down a posting to Egypt on account of her mother’s failing health.

Following her military service Cathie worked as a clerk-typist at the Brierton Hospital and Chest Clinic (the “isolation hospital”) in Brierton Lane from 12th February 1951 to 28th October 1952. Following this she took a position as a civilian clerk-typist with Durham County Constabulary, working for the Criminal Investigation Department based at the West Hartlepool Police Station. During Cathie’s tenure CID was headed by Detective Inspector Jack Waiton. He was assisted by Detective Sergeant Fred Bennett. Mr. Harold Coyne was Chief Inspector and the Superintendent was Mr. Reg Hammond.

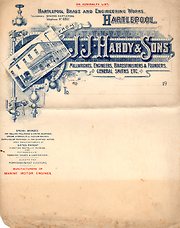

It was while working at the Police Station that Cath made a lifelong friend, Mrs Minnie Boyle (nee Baines), a descendant of the founder of J. J. Hardy’s brass foundry where Cath’s husband had his first job as a 14-year old boy. Minnie, of Linden Grove, worked on the switchboard and was an ex-WREN. She later became a social worker, married (an ICI chemist and former Lieutenant in the Royal Navy) and moved to Millom in Cumbria.

Cathie Ross met Jim Wilson (1927-94), a marine engineer, at the local Queen’s Rink dancehall. Their eyes met across a crowded dance floor, Jim cut in and that was that. The couple married at All Saints Church, Stranton, on the 28th of August, 1954. The bride was given away by her eldest brother, Walter, her dress was made for her by her mother and the marriage was witnessed by Jim’s brother-in-law, Bill Fawley, and Cathie’s cousin, Lil Jervis (daughter of Bill and Lil). Jim and Cathie had one son, Stuart James Wilson (born 17th November, 1964). Jim Wilson had a distinguished career in engineering, both at sea and ashore, and his biography is given separately.

The couple lived first, for a short time, with Cathie’s mother at 31 Wordsworth Avenue, before moving to their own home at 125 Raby Road. In the early Sixties they moved to & Bournemouth Drive, Hart station, moving again in 1967 to the Fens Estate. All of their homes were privately owned and the latter two were newly built. Both Jim and Cath were talented amateur artists, taking up the hobby in earnest from the early 1970s. They both became members of the local art club with paintings shown in the local open art exhibitions. Cath attended leisure classes at the Hartlepool College of Art.

Source: (1) “The Ross family and Others” by Stuart James Wilson; (2) “The Wilsons of Whitby and West Hartlepool,” Vol. 6 by Stuart James Wilson.

More detail »

Biography of Edgar Wilson

Biography of Edgar Wilson

Charles Edgar Coates Wilson

Born on 16th January 1903, “Edgar,” as he was known, served an engineering apprenticeship before going to sea as an engineer-officer in the Merchant Navy, rising to the rank of Chief Engineer (Extra First Class). At the outset of his seagoing career he sailed for Furness, Withy as a junior engineer aboard the “London Merchant” (which later, as the “Politician,” was the inspiration for Sir Compton Mackenzie’s “Whisky Galore”), departing from Manchester. In the winter of 1927 Edgar Wilson left England for a sojourn in India, sailing as Third Engineer aboard the tramp steamer “Akbar” (Bombay & Persia Steam Navigation Co.). Pay on foreign service was much higher than in home waters and the social life of a ship’s officer on the Indian coast was good. Edgar was also employed in a junior managerial position ashore whilst in India, working in a shipyard or engineering shop.

After his time away he worked his passage home as Fourth Engineer of the tramp steamer “Torbeath.” Upon his return he was taken very ill, convalescing at the family home. Subsequent appointments comprised:

March 1930: Third Refrigeration Engineer aboard “Highland Monarch,” from London to South America via France and Portugal.

February 1930: Third Engineer aboard twin-screw cargo liner “Tairoa.”

May 1930-January 1931: Second Refrigeration Officer aboard the “Murillo,” then Third Engineer aboard “Meissonier.” Both ships sailed out to South Africa, from London and Shields respectively, returning to London and Southampton.

January 1931-October 1937: Second Engineer aboard the steamer “Kirnwood,” sailing from ports in Northern England and South Wales bound for Canada.

Edgar married Florence Annie Fowler Cowley, a 27-year old clerk with the local Co-op society, at the Westbourne Methodist Church, West Hartlepool, on 7 March 1932. Flo, as she was known, administered the Co-op dividend from the offices of their main store on the corner of Park Road and Stockton Street. She was the daughter of George Cowley, a local Police Constable. Edgar and Flo lived firstly at the Wilsons’ summer house at Dalton-on-Tees, subsequently moving to Alverstone Avenue and then, prior to outbreak of the Second World War, to 39 Greta Avenue, West Hartlepool. The couple had two daughters, Joan (born 1937) and Anne (born 1938).

From May-September 1938 Edgar sailed as 2nd Engineer aboard the steam tramp “Ousebridge,” owned by the West Hartlepool shipping company of Crosby, Magee & Co. His next ship was the “New Westminster City,” fitted with triple-expansion machinery from the Central Marine Engine Works. Edgar signed off this ship as Second Engineer at Liverpool just six days after Britain declared war on Germany. He spent a precious three weeks at home with his family before returning to sea, joining the tramp steamer “Saltersgate” at Cardiff as Chief Engineer.

In June 1940 the Nazis were sweeping across France and “Saltersgate,” under the command of Captain Stubbs, and with Edgar Wilson as “Chief,” was ordered to evacuate wealthy British expatriates from the French Riviera. The 700 evacuees, one of which was the writer W. Somerset Maugham, were united in their glowing praise for the selfless conduct of the ship’s 36-strong crew under the most gruelling of conditions.

Excerpts from personal testimonials sent to Edgar’s wife read as follows:

“I have such grateful memories of your husband’s kindness to myself on his ship . . . I won’t ever forget it.” A second wrote that “We all thought the world of our Chief Engineer. Don’t tell him this – for it upsets his sense of modesty – but I think you are a lucky woman and he thinks he is a lucky man to have such a good wife. With a deep sense of gratitude for his kindness. . . .” A third wrote of having “found new friendships . . . with those of the Engineer Officers’ mess. Thanks Chief! You hate flattery and I can’t say this to your face but I can honestly and sincerely write you’re one of the kindest men I’ve been privileged to know.” A fourth wrote of “a laurel wreath for patience and endurance awarded to our Chief Engineer!!!”

The story has it that upon going aboard the humble tramp ship, one elderly aristocratic lady, obviously used to better things, enquired as to the location of the “games deck.” “It’s all over the ship, madam!” replied the ship’s steward. Nevertheless, contemporary newspaper-cuttings etc. (e.g. “The Joke of the Cream” by William Hickey, “Daily Express,” Monday, July 15 1940) attest to the shocking overcrowding, the want of water, cabins given over to invalids and a possible submarine attack during the voyage home to Liverpool. Upon docking, three cheers were raised for the crew of the “Saltersgate” in recognition of all they had done. “Saltergate” went on to play a part in the D-Day landings, as part of the “Mulberry Harbour.”

From July 1941 to March 1943 Edgar was Chief Engineer aboard the “Clumberhall,” a Gray-built steamer owned by the West Hartlepool Steam Navigation Co. In December 1941 the ship encountered very heavy weather in the North Atlantic. Coal sometimes ran short, leaving some ships no choice but to take on either the bare minimum or an inferior grade. As a consequence, the “Clumberhall” ran short of fuel whilst westbound, leaving her a sitting duck for any prowling U-boat. Luckily, she was towed into St. John’s Newfoundland, by the Admiralty tug “Prudent” (the episode did not reflect badly upon Edgar, whose Discharge Book shows nothing but the highest praise for conduct and ability.

From July 1943 until the end of the war Edgar was Chief Engineer aboard the “Empire Torridge.” He received the 1939-43 Star for his war work, most of which involved the North Atlantic convoys. After the war the “Empire Torridge” was bought by the Kyriakides Shipping Co. and renamed “Huntress.” She was then crewed by British officers and seamen, but the engine-room and stokehold crews were Hong Kong Chinese. Edgar continued to sail as Chief Engineer aboard the “Huntress” until his 47th birthday. At times, his wife and daughters accompanied him.

He left the “Huntress” to sail mostly on coastal and short-sea routes, but eventually left the Merchant Navy due to ill health, being discharged from his ship at Quebec. Ashore, Edgar became Shift Manager at the North Tees Power Station, Stockton-on-Tees. He passed away on 1 August 1971. Edgar was cremated and his ashes were scattered in the Garden of Remembrance, Stranton Grange Cemetery, Hartlepool.

Source: “The Wilsons of Whitby and West Hartlepool,” Vol. 4 by Stuart James Wilson. See images.

More detail »

Biography of Eric Wilson

Biography of Eric Wilson

Eric Norman Wilson

Eric was born in 1915 and in an incident reminiscent of the famous story concerning Oliver Cromwell, he too was seized in infancy by a pet monkey! The animal was purchased by Eric’s father, Thomas George Wilson, during one of his voyages as a seagoing Chief Engineer. Named “McTavish,” it was normally kept in a cage dressed in a small kilt. In an impudent display of malicious contempt for its human captors, and a fury born of its confinement, the hairy little “Scotsman” had a habit of raising the hem of its tartan garment to spray the contents of a full bladder through the wire bars! During a rare moment of freedom the monkey took a liking to little Eric’s baby clothes and became quite agitated when the little lad wouldn’t part with them. Eric’s mother rescued her infant son from the struggle and, thankfully, the pet wasn’t subject to the same punishment as its legendary Hartlepudlian predecessor.

Like his elder brother, James, Eric Wilson became an articled clerk at Fortune’s accountancy practice, Collingwood House, Church Street, West Hartlepool. During the Second World War he served with the Cameronians, also known as the Scottish Rifles, and was first assigned to Balmoral Castle, where his duties included guarding the then Queen Elizabeth. He took part in mountain warfare training, comprising climbing and skiing, but his active service was spent in Holland (typical Army!). His unit was due to go to Arnhem, as part of Operation Market Garden, by towed assault glider. Thankfully, bad weather delayed the flight, preventing the men from playing any significant part in that ill-fated assault.

Eric was eventually invalided out of Holland with pneumonia but upon his recovery was seconded to the Allied & Military Government of Occupied Territory (AMGOT) on administrative duties. He also spent time as a regimental policeman. After his “demob” Eric found employment at West Hartlepool’s steelworks, working as a semi-skilled fitter’s mate but earning more money than in his previous white-collar position as a clerk.

In his retirement Eric and his wife Irene (nee Lendrem) lived at Hamsterley Village in County Durham before moving to a care home near Bishop Auckland. The couple met in West Hartlepool’s Ward Jackson Park. Eric and a friend spotted two girls, persuading his friend to go over and ask them out. When first married the couple “lived in” with Eric’s mother for a while before moving to homes in Ashley Gardens, Catcote Road and Carr Street, the latter being left to them by the Lendrem family. Irene worked for many years as a school-crossing lady, cycling three times daily to the Owton Lodge. It was a job she loved.

Card players and keen cyclists, Eric and Irene frequently took to the countryside on their tandem bike. Though of a retiring disposition, Eric was once a frequent letter writer to the local paper and in his younger days he was also a keen sportsman, playing amateur rugby and cricket, in the latter case for the steelworks.

Eric and Irene Wilson had two children, Maureen and Derek Gordon. Both became teachers and both attended the Wesley Youth Club as members of the Concert Party. As a youngster Derek Wilson was given a book on meteorology as a birthday-gift from his parents. At the age of fourteen he became the youngest accredited rainfall observer in the country, being featured in the local newspaper. He also met the then Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, during an official visit to the Hartlepools. Derek began his working life as a weather forecaster at the Middleton St. George airport near Darlington. Sadly, he died at the age of just thirty-two, the victim of a massive epileptic fit in a bed-sit at Greenford in London, during the Silver Jubilee year, 1977. He was laid to rest in Stranton Grange Cemetery, Hartlepool and is remembered by another family member as the archetypal student, with long knitted scarf and a curly mop of bright red hair.

Eric and Irene Wilson celebrated their Diamond Wedding Anniversary in 2001. Irene passed away two years later and Eric followed in 2004.

Source: “The Wilsons of Whitby and West Hartlepool,” Vol. 4 by Stuart James Wilson. See also images.

More detail »

Biography of James Wilson Pallin

Biography of James Wilson Pallin

JAMES WILSON PALLIN

James Wilson Pallin was the first child of Thomas Harriman Pallin and his wife Maria Elizabeth (nee Wilson). He was born at Blackburn on 8 May 1887, completing his apprenticeship as a shipwright at West Hartlepool. During the Great War he volunteered for duty, serving as a First Class Petty Officer in the Royal Navy aboard the depot ships “Swiftsure” and “Vulcan.” On cessation of hostilities he sailed as a ship’s carpenter in the Merchant Navy aboard the steamer “Mandalay.” Whilst outward-bound to Australia he was swept overboard and back again, sustaining injuries that saw him hospitalised.

He left the sea and took a job with Gray’s shipyard, West Hartlepool, being one of those that worked on the paddle-steamer “Wingfield Castle.” Ostensibly quite austere, he was a practising Methodist, having signed “the Pledge” as a teetotaller. Nevertheless, he was a kindly man and apprentices found him eager to pass on his skills. Jim Pallin sang in the Orpheus Male Voice Choir (formed 1910) and during the 1920s and 30s the choir achieved great success in national competitions. His workmate Charlie Crinson was also a member of the choir as the two are remembered as singing while they worked.

James Pallin married Ann Isabella Murphy. The couple lived at 31 Grosvenor Street and had three children, two girls (later Mesdames Kerridge and Hauxwell respectively) and a boy (who sadly died in infancy). Jim’s son-in-law, Arthur Hauxwell, a fitter-and-turner by trade who served his apprenticeship at Richardsons, Westgarth, was notable for his book “I Am Not a Tramp!” about his charity walk from Land’s End to John O’Groats. Jim Pallin later worked for F. O. Kindberg & Co., a firm of ship and boat repairers engaged in maintaining the so-called “Mothball Fleet.”

Source: “The Wilsons of Whitby and West Hartlepool,” Vol. 3 by Stuart James Wilson. See images.

More detail »

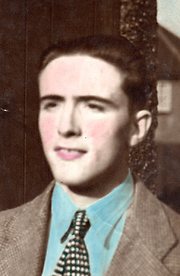

Biography of Jim Wilson

Biography of Jim Wilson

JIM WILSON, C.Eng., M.I.Mar.E.

EARLY YEARS

Jim was born on the 29th of September 1927, the second child and first son of James and Elizabeth Wilson, then of 25 Ladysmith Street on the outskirts of the Longhill Estate. This was situated close by the North Works of the South Durham Steel & Iron Co., where his father worked as a clerk. Jim Wilson had an early introduction to the sea. His father would often hire a fishing coble from Middleton and young Jim accompanied him as soon as he was old enough. There were trips to see the Royal Navy battle-cruiser “Hood” (6-9th September 1932) and Hartlepool’s prehistoric submerged forest of Longscar Rocks. Another memory was of the German airship “Graf Zeppelin” which flew over the Hartlepools on 19 August 1931, its massive engines rattling the windows of the Wilsons’ home at 7 Elcho Street.

SCHOOLING AND BOYHOOD

Jim attended Lynnfield and Elwick Road schools. He was an active child, playing football and cricket for the school teams, as goalkeeper and wicket keeper respectively, coming in to bat at “first-wicket down.” During the inter-war years Jim’s father was convinced that further conflict with Germany was inevitable. As a result, he put his eldest son through a punishing fitness regime as preparation. This included running on the sands with a rucksack full of bricks! Jim Wilson was one of the Lynnfield school team that won the junior cricket league and cup in 1939.

Young Jim was never comfortable with the heavy hand of authority and determined to leave school at the earliest opportunity. Schools of Jim’s era were militaristic in nature and Lynnfield particularly so. The school hall boasted prints of the German battle-cruiser “Blucher,” a participant in the Bombardment of the Hartlepools, sinking at the Battle of the Dogger Bank and Lady Butler’s “Charge of the Scots Greys” at Waterloo. Even so, Jim managed to pick up prizes for drawing and craftsmanship. Jim might not have liked school, but he always enjoyed learning and was an avid collector and reader of books on maritime and technical subjects.

Jim was determined to become a marine engineer like his uncles and grandfather. He deliberately flunked his scholarship in order that the extra two years of study this would otherwise have entailed should not delay his entry into the engineering industry – and also to avoid staying on at school! The decision met with no small disapproval from his mother and when he swaggered off for his first day at work, age 14 and in a boiler suit far too big for him, she was heartbroken.

Always wilful, Jim’s determination to pursue a goal is demonstrated by a story from the war. He was out collecting sea coal one morning for his parents with an old pram when he spotted a wireless-telegraphy set washed up on the beach. It seems to have come from a German bomber shot down in Hartlepool Bay. The area, however, was mined and cordoned off. Jim was intent on the trophy, other children contenting themselves with bits of shrapnel and the like. After creeping under the barbed wire he was successful. No mines exploded on that occasion – but his mother did when she learned of the exploit!

PRE-APPRENTICESHIP: J. J. HARDY & Co.

In 1973 Jim wrote an account of his first job as a fitting-shop boy at J. J. Hardy’s brass-founders, “Old Hartlepool,” and extracts are as follows:

“From the tender age of nine years I wanted to be an engineer. I joined the local Public Library by lying about my age (one was supposed to be eleven). As soon as I could . . . I was reading Macgibbon’s and Sothern’s marine engineering books. As a consequence, I understood a fair amount of the technology of the steam engine before I started work at the age of fourteen years.

“During the schooling of my era one was taught discipline and regimented obedience (i.e. the class system of ‘obeyers and obeyed’). The ‘bosses’ and ‘men’ both called each other b------s . . . little realising that each were only human beings all having personal commitments of varying degrees.

“The area in which I was born was predominantly marine- engineering and shipbuilding based. The U-boat campaign was at its height, and with this as a back-cloth I set out to my job at a small brass-founders and engineering shop in the autumn of 1941.

“First things first. The manager, a Mr. Walker, showed me into his office. Every morning at 8 am I was to set and light the coal fires in his and the accountant’s offices (upstairs), followed by sweeping out of the small fitting shop – occupied by one old fitter-turner, three lathes, one boring machine and two drilling machines. In addition I had to learn to use the two smaller of the unoccupied lathes. My function at 12 noon and 5 pm was, on the hour, to ring the bell that signalled finishing times for ‘dinner’ and ‘tea. . . .’

“Every night on completion of work one had to fill in a time-board. This piece of unhygienic material was a piece of wood with the personal works number stamped on and whitewashed on one side (whitewash! – a mixture of spit and chalk allowed to dry). . . .

“The original intention of the manager was to allow me six weeks in which to learn to use the lathe, but in the tool cupboard of this machine I found some pre-war copies of the “Model Engineer” with an article on how to make a model crankshaft. I armed myself with this, a piece of scrap steel bar and considerable tutelage from Mr. [Thomas] Appleton, the old fitter-turner. After three weeks the manager walked out into the shop, watched me using the machine and posed the question: ‘What’s that you’re making?’ Informing him that it was a model crankshaft, my enthusiasm was dampened somewhat on being told: ‘OK, you can use it. Now chuck that out, I’ve got a job for you.’

“I still recall the job I was given to do. It was to machine the ‘dogs’ off a steam winch clutch for a collier, the s.s. “Melbourne.” After this there followed a succession of jobs and I became proficient in the use of tools etc. – the most prominent [job] being a potato-peeling machine for a local fish-and-chip shop, another (more sophisticated) potato-peeling machine for a restaurant (this m/c required new [bearing] ball-races) and a piece-work contract for the Admiralty. The latter consisted of drilling and tapping 150 ¼” diameter holes (through a jig supplied by the Admiralty) in ¼” thick armour plate, to cover the engine-room skylights of armed trawlers and minesweepers (considered necessary after several aerial machine-gunning incidents in the North Sea).

“This period before my apprenticeship provided me with good experience, tempered by ‘light reliefs’ such as every Friday going for Mr. Appleton’s five ‘Manikin’ cigars and two ounces of ‘Stag: snuff, for which he gave me 6d pocket money . . . and, with the shop-boy from the brass-finishing department, obtaining, for the manager 40 ‘Players’ cigarettes per day. Not so easy as it sounds, because shopkeepers rationed their customers. But as we scrounged round the ‘old part’ shopkeepers soon got to know us and we didn’t do so badly (picking up the smoking habit ourselves in the process).

“Mr. Appleton . . . proved to be a craftsman of the highest order. Amongst various teachings he showed me how to make, harden and grind lathe tools and chisels from plain tool steel bar, also pressure gauge making, all of which I found served me well later in my career. Incidentally, every gauge he tested and set he marked on the back cover his initials and the date. Many years later I received a rare surprise.

“Labour relations in this small works were quite good. The men called the manager ‘Tot’ and he called them by first names, the only cloud in the sky was when the chairman came to visit. Then it was as though a step backwards had been taken and the relationship was one local squire and his tenants. . . .

“Having applied for an apprenticeship at a local marine engineering works when I was twelve years old and having been accepted, I left the small works with slight regret and, armed with the experience obtained there, stepped forth to serve my time at sixteen years of age.”

APPRENTICESHIP: CENTRAL MARINE ENGINE WORKS

Jim served his five-year apprenticeship at the Central Marine Engine Works of Wm. Gray & Co., West Hartlepool from 1943-48. Of this he wrote that his:

“apprenticeship was served at the only self-contained engineering works in the whole area, in that it had its own brass foundry, iron foundry, boiler shop and bar shop, plus a forge. It even manufactured studs, nuts and bolts. The only bought-out items were raw materials – steel slab, bar and rod, coke and pig iron for the iron foundry etc.

“Indentures read like a page from a Dickens novel – ‘Will obey the master’s lawful commands’ etc. . . . everything on the side of ‘the master.’ . . . Unfortunately, the firm did not survive the crunch in shipbuilding in the early 1960’s, but what a place to learn a trade. There will never be another works like it . . . the finest on the NE coast. One started as a revenue-earning unit straight away on the shop floor, it being the policy . . . for apprentices to have at least 18 months turning work on centre and chuck lathes to start with. On my first day I was put with another youth who was working a large chuck-lathe turning the fork-end pins to fine tolerances on a set of tug engine valve-gear slide bars. My previous experience showed, and the youth who was to teach me was shifted elsewhere after only two days instead of the usual week. Discipline was very harsh. The management closed its eyes to ‘the herd’ having a drink of tea at 10 am. No one dare move to put their tea cans on the fire for a warm until old ‘Monty’ the Works Manager had his walk round the works between 9 and 10 am.

“Very occasionally someone stole a march on the rest and put a can on the fire before 9 am. If Monty saw a can there he would stand by the fire until the tea can boiled over, and then walk away with a smile on his face. I don’t think any such incident ‘made his day,’ . . . he was just demonstrating who was boss.”

On the signing of Jim’s indentures the Works manager, Mr. Marmont (“Monty”) Warren, known as “Buddha” due to his corpulent physique, concluded with a “Well son, make yourself into a good engineer.” “Yes Mr. Warren,” replied Jim, dutifully, and promptly did exactly that.

Later, in 1992/93 Jim wrote of his marine-engineering apprenticeship that:

“Over the eighteen months spent in the Machine Shops, machined parts increased in complexity until one was a competent machinist with the ability to work to fine tolerances from workshop drawings. Then started the fitting phase of your apprenticeship.

To increase production the main propulsion engines were divided into sub-assemblies where possible, and the engines erected as a whole unit in the Engine Erecting Shops. It was the practice of the Company’s Apprenticeship Programme to work on the sub-assemblies on a rota system in the shop, and then work on the whole engine assembly and erection. This being good practice as one learned the whole process of engine manufacture from marking off and lining out to completion.

The rota system applied in the various designated workshops throughout the works. The Auxiliaries Shop manufactured . . . plant for marine and land use and dealt with reciprocating pumps, centrifugal pumps, feed-water heaters, coolers, evaporators, ash-hoist systems, valves and small condensers.

“On reaching the last years of your apprenticeship one was sent to the Fitting Out Department concerning the fitting of plant and machinery into ships. On completion, the plant and machinery was tested to satisfy Classification Society surveyors and a seaworthiness certificate issued. The ship was . . . taken to sea and full power trials conducted. Usually on sea trials six apprentices were available in the engine room, and with the number of ships being built at that time it was not unusual to attain three trial trips before completion of your apprenticeship. . . .

“During the course of your apprenticeship the apprentice had contact with all the offices and workshops, gaining valuable knowledge and experience of other processes although not directly involved. Retrospectively one would consider the outstanding merit of the engineering apprenticeship was to instil confidence and attain the skills to perform the given task.”

Jim makes no mention of the long hours, attendance at night-school and hard physical labour that was expected, in the latter case such as tightening up enormous propeller nuts with a sledgehammer. In an interview with the “Yorkshire Post” newspaper (11th January 1988) he also commented that fitting-out conditions were often terrible: “When I was at Gray’s they didn’t even have electric light [for work aboard ship]. The first thing you did in the morning was to draw two candles from the stores. You had to use them everywhere, even in the bottom of a boiler – you can imagine what it was like.”

Jim continues that:

“The fifth year of my apprenticeship was the year in which I had my first full responsibilities. The ship on which I was working at the time [the s.s. “Erik Banck”] was nearing completion and was due to go on sea trials before handover to the customer, when the fitting out workforce decided to go on strike.

“Being a ‘bound’ apprentice and at that time a senior . . . I was requested to choose six other apprentices and take the ship to sea on sea trials by the Departmental Manager and Foreman and thus under their guidance and with the instruction of the Lloyd’s surveyor we completed successful sea trails and the ship was handed over to the customer on time.”

ENGINEER-OFFICER IN THE MERCHANT NAVY

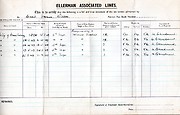

Jim writes that unbeknownst to him he was due to be transferred to the design office. However, he had already applied to Ellerman’s City Line for a position as a seagoing engineer and had been accepted. Whilst visiting the offices he’d noticed a broken windowpane. A shaft of brilliant sunlight shone through the little hole, and in it were illuminated a thousand tiny dust particles. It was then that he made up his mind to go to sea. He was interviewed and accepted as an engineer-officer in the Merchant Navy at Middlesbrough’s Mercantile Marine Office on 9 October 1948.

Jim subsequently sailed as a Junior Engineer aboard Ellerman’s “City of Canterbury” and the Clan Line’s “Clan Macrae.” The former, a passenger ship, sailed from the UK to East Africa via the Cape of Good Hope, her main port of call being Capetown. The latter, a cargo liner, steamed out to Australia via the Suez Canal. This meant a passage through the dull-grey Atlantic to Gibraltar, then into the sunny Mediterranean. Anchored at Port Said, the ship would be surrounded by bustling “bum-boats” selling their dubious wares and there too was the song of the Arab “coolies” as they set about their labours and the wailing cry of a holy man, floating out from a sun-bleached minaret and calling the faithful to prayer. After passing through the Suez Canal the ship made for the arid port of Aden, passing through the Straits of Bab-el-Mandeb (the “Bridge of Tears”), with its flying fish.

Jim’s seagoing career included the usual nautical adventures, including:

(1) Putting on a canvas diving suit, with brass helmet and lead boots, to inspect a damaged propeller in the Indian Ocean. He volunteered and was swung overboard in a shark cage.

(2) Taking part in a sea rescue when a sister ship lost her rudder in the Bay of Biscay.

(3) Foiling a smuggling plot to incriminate ships’ officers.

(4) Nearly being lost when his ship encountered a tempest in the Indian Ocean.

With regard to the latter, Jim well remembered the terrible, howling violence of that storm. To hear him tell it was almost to have been there with him. You felt the crazy motion of the deck under your feet, the ship shuddering and reverberating as giant 60-ft waves crashed against her. You saw, as Jim had seen, the paint flaking away from around the rivet-heads as hull plates worked against each other. You felt the tension and the fear – and the need not to show it. Finally, Jim described the eerie serenity that followed in the wake of that furious tempest.

Notably, Jim had a lifelong hatred of the South African authorities for their treatment of blacks. He regularly courted trouble during his visits to South Africa and on one occasion was fined for assaulting a sergeant in a South African police station. It was Jim’s birthday and he’d been out drinking ashore with shipmates.

Deciding to make his way back to the docks he was picked up by the local constabulary and taken in for some rough questioning by the desk sergeant. Jim responded with a flying head-butt that settled the obese policeman but was then subject to a thorough ‘working over’ by the man’s colleagues. Slung in a cell, he got talking to the other inmate. This man happened to be a white club-owner who was frequently harassed by the authorities due to his favourable treatment of black employees. After giving him his card, the man sent Jim round to his club upon his release the next day and it was there that Jim’s injuries were treated.

The incident was later reported in the local newspaper as “Drunken Scotsman on Birthday Spree!” Jim’s name was also given as “Wilson James” (in the style he’d answered the magistrate). During his court appearance Jim was asked if he wished an officer to speak for him. “But I am an officer!” protested an outraged Jim, to the amusement of the court. Given a choice between hard labour and a fine, he opted for the latter. Jim later discovered that the desk sergeant was an ex Nazi SS NCO.

Jim was always very handy with his fists, being taught to box by Terry Allen, a childhood friend that later lost an arm in a shunting accident on the railway. A second noteworthy incident concerned the knocking-out of a particularly offensive drunk on the platform at Euston Station – to the polite applause of onlookers!

In one of his letters home, sent from London’ Royal Albert Dock and dated 4-12-48, Jim wrote that he wished his younger brother could have seen Liverpool Docks:

“when the fog cleared there was nearly 60 ships that we counted, it was like being in a convoy. As soon as it lifted it was Up Anchor and the devil take the hindmost. . . . In one of my shipping books you will see a photo of the liner “Canton;” well she passed us inward bound with passengers from the Far East. There’s Ellerman Wilson ships, Brocklebanks, B.I. (British India), P & O, Blue Star, Shaw Savill & Albion, Union Castle, Royal Mail, Cunard and the “Umaria” of the BI, built by us, has just come in.”

In another letter, sent from Durban and written on 15.1.49 he wrote: “How I will get this letter posted I do not know. There are big riots on here. The Zulus are attacking the Hindus. . . . Our crew are not allowed ashore.” He continues that he’s seen a white policeman “with his head crushed in from a blow by a knobkerrie” and also a Hindu, whilst “One poor feller” was “dragged along by his feet over cobbles” being kicked and battered. The night before had been pay night and the black dockers “were crazed with illicit beer and daggu, a drug like hashish. . . . The carpenter was coming back to the ship last night and had to drop flat when the Hindus started shooting at Zulu dockers. There’s a sort of deathly silence over the place – it’s a bloody awful feeling. We are shifting ship over toward a native quarter so I’m stopping aboard where I am safe. Everybody is just hanging round the street corners waiting for something to happen. . . . . You should see them chanting war songs and shouting war cries like this Yi-yi-yi-yooeee.”

Jim was specially commended for his efficiency during his time aboard the “City of Canterbury” and wrote of his time at sea that:

“Virtually no training was given and more or less you were expected to know what you were doing. My first appointment was ‘days at sea’ – ‘nightshift in port.’ On ‘nights,’ which lasted from 7pm to 7am some of the machinery and plant was running the whole time in port, and it was your duty to check temperatures, pressures and oversee the lubrication (attended by a greaser) and the working boilers with what was known as a ‘Donkeyman.’ The company I joined had ethnic crews but fortunately an ex-engineer of the British India Steamship Company taught me some Hindustani during my apprenticeship and I was able to communicate effectively with them.

“Later when promoted to watch-keeping engineer, a daily log was kept which was meticulously completed each watch, and a voyage report on the performance of the plant and machinery. Although at that time no formal planned maintenance was carried out, what would probably termed “discretionary” maintenance in foreign ports, planned by the Chief Engineer and implemented by ourselves (the ship’s engineers) to prevent breakdowns and prepare for the voyage home, was used.”

Having an enquiring mind, Jim decided that a continued career at sea, and “the maintenance of old machinery,” was not for him.

“RICHIES”

Jim Wilson was very proud of “serving his time” at “the Central,” but it was said of him that if you cut him through the middle you’d find “Richardsons, Westgarth” printed there like a stick of rock! Jim joined R.W. as a fitter in 1951 and was quickly promoted to supervisory level. He wrote that:

“I was concerned with constructing marine [steam] turbines . . .” also fitting them aboard tankers built by the Furness Shipyard at Haverton Hill. He also performed over-speed shop tests and worked on the “land side,” of which Jim wrote that: “The company built Brown-Boveri turbo-alternators for power stations and was very successful,” their machinery producing 550 MW from a single shaft. For Jim the years 1956 to 1966 were “an exciting era of change and progression and being involved in the developments taking place was very rewarding.”

Engine erection planning was one of Jim’s responsibilities but, again, no formal training was given in supervisory duties, employers relying upon “professional skills, ability, judgment and common sense. . . .” Jim did note, however, the quality assurance scheme introduced by the Central Electricity Generating Board, a Work Study scheme and various RW standards that were documented with regard to fabrication, pipework erection etc.

Jim wrote that: “until around 1956 commercial marine propulsion units were standardised at around 8,500 shaft-horse-power,” rising within ten years to 29,500 s.h.p. There were “occasional attendances at sea trials, guarantee surveys and Classification Society surveys as company representative engineer. During these periodic visits to various engines [on the Tyne, for example] it was the practice to ‘open up’ the turbines to inspect the blading and internals.

“The overhauling equipment used to support the top half of the cylinders was cast iron, as was the rotor guides, and was very heavy to position on the bottom half cylinder joint. I resolved to redesign this equipment at the earliest opportunity. On investigating the design of these items I found that [it] originated from an Admiralty design dated 1905. With the advent of welded steel fabrication using thick-wall steel tubing and . . . plate, weight was reduced by half on both items for a similar strength-cost factor and was adopted for future sets.”

In 1953 Jim supervised the erection and fitting of main machinery for the tanker “Melika.” This vessel was later involved in an incident, as referred to by Peter Hogg in his history of Richardsons, Westgarth. She was abandoned while steaming by her crew owing to a fire, being recovered by the Royal Navy. A survey at Bombay revealed that in spite of the main machinery not having been progressively cooled as a result of her emergency shut-down, the shaft alignment remained perfect. Hogg writes that this was testament to the high quality of British marine engineering at RW.

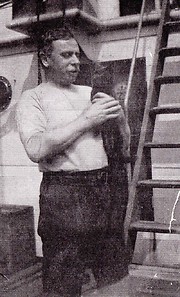

Jim is pictured on p. 62 of Hogg’s book, working on a high-pressure turbine rotor in boiler-suit and characteristic white roll-neck jersey. In addition to steam turbines, whilst at “Richies” Jim also worked on North-Eastern Marine Doxford diesel engines built by RW between 1945 and 1957.