Hartlepool Sports & Leisure

Hartlepool Sports & Leisure

- Cinemas, Theatres & Dance Halls

- Musicians & Bands

- At the Seaside

- Parks & Gardens

- Caravans & Camping

- Sport

Hartlepool Transport

Hartlepool Transport

- Airfields & Aircraft

- Railways

- Buses & Commercial Vehicles

- Cars & Motorbikes

- The Ferry

- Horse drawn vehicles

A Potted History Of Hartlepool

A Potted History Of Hartlepool

- Unidentified images

- Sources of information

- Archaeology & Ancient History

- Local Government

- Printed Notices & Papers

- Aerial Photographs

- Events, Visitors & VIPs

Hartlepool Trade & Industry

Hartlepool Trade & Industry

- Trade Fairs

- Local businesses

- Iron & Steel

- Shops & Shopping

- Fishing industry

- Farming & Rural Landscape

- Pubs, Clubs & Hotels

Hartlepool Health & Education

Hartlepool Health & Education

- Schools & Colleges

- Hospitals & Workhouses

- Public Health & Utilities

- Ambulance Service

- Police Services

- Fire Services

Hartlepool People

Hartlepool People

Hartlepool Places

Hartlepool Places

Hartlepool at War

Hartlepool at War

Hartlepool Ships & Shipping

Hartlepool Ships & Shipping

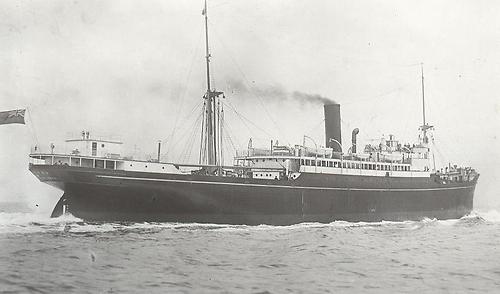

Digby

Names and owners

Year |

Name |

Owner |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1912 | Digby | Furness Withy & Co. Ltd. | |

| 1915 | Artois | French Government | |

| 1917 | Digby | Unknown | |

| 1925 | Dominica | Bermuda & West Indies S.S. Co. | |

| 1936 | Baltrover | United Baltic Corp. | |

| 1947 | Ionia | Hellenic Mediterranean Lines. | |

| 1965 | Ionian | S.E. Asia Shipping & Trading Co. |

Fate

Capsized at Jakarta, Indonesia, on July 26th, 1965 and was later broken-up.

Related items :

Dominica

Dominica

Created by unknown

Donated by Mr. Derek Longly

Created by unknown

Donated by Mr. Derek LonglyPostcard of the Dominica, originally built as the Digby.

More detail » Furness Withy & Co. Ltd.

Furness Withy & Co. Ltd.

Christopher Furness was born at New Stranton, West Hartlepool, in 1852, the youngest of seven children. He became a very astute businessman, and by the age of eighteen was playing a major role in his older brother Thomas’ wholesale grocery business, being made partner in 1872.

In 1882 the two brothers decided to go their separate ways, allowing Thomas to concentrate on the grocery business, while Christopher took over the ownership and management of the four steamships their company was then operating.

This was the beginning of what would eventually become the huge Furness Withy & Co. Ltd. empire. As many books have been written detailing the history of this company, its ships and its many subsidiaries, this section will only feature those ships with direct Hartlepool connections.

Some of the ships that were not built at Hartlepool but owned by Furness are listed below as 'a general history'

More detail »

Ionia

Ionia

Created by unknown

Donated by Mr. Derek Longly

Created by unknown

Donated by Mr. Derek LonglyA view of the Ionia leaving/entering port and looking very smart indeed.

More detail » Ionia - Boat Deck

Ionia - Boat Deck

Created by unknown

Donated by Mr. Derek Longly

Created by unknown

Donated by Mr. Derek LonglyA view of the lifeboats on the Ionia's boat deck.

More detail » Ionia - the Bar

Ionia - the Bar

Created by unknown

Donated by Mr. Derek Longly

Created by unknown

Donated by Mr. Derek LonglyA view of the Ionia's bar.

More detail » Memories of a sea passage on the Ionia

Memories of a sea passage on the Ionia

MEMORIES OF A SEA PASSAGE ON THE “IONIA”

There was much excitement in the offices of the agents for Hellenic Mediterranean Lines on the quayside at Limassol, Cyprus on the afternoon of the 22nd July 1961 where, having made my way to the shipping agency from Episkopi, and having paid the money due, I had had my luggage labelled, and joined a group of other prospective passengers who were either sat on their cases and trunks in the hot, stuffy room, or leaning against the peeling paint and torn posters on the walls fanning themselves with whatever was available. Today was sailing day for the scheduled departure of one of the company’s ships serving on its route linking Marseilles in France with the countries of the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa.

The local agent, a large florid figure in a crumpled suit, mopped sweat from his face as he shouted instructions in Greek at various uniformed officials and assistants. The fact that disembarking passengers were becoming muddled in with those due to go aboard was not helping keep the atmosphere calm. Items of luggage were being hoisted onto the brown shoulders of porters with careless abandon as to whether their owners were going to board the waiting ship or had just left it, which merely added to the general confusion. At a table set in a corner of the room serious faced customs officials sipped Turkish coffee or glasses of water, ignoring the upheaval, as they carefully, and very thoroughly, checked traveller’s passports, clearly having difficulty with those belonging to the more excitable and voluble passengers listed on the manifest.

Matters seemed to reach a crescendo of noise and activity after an hour or more, then suddenly the crisis was over, the customs officials took formal leave of the agent, the agent undid the collar of his shirt and relaxed in a perspiring heap, whilst the arriving passengers were all accounted for, rounded up and separated from those waiting to board. Two large wooden doors were opened on the seaward side of the office to reveal a short length of wooden jetty at which awaited an antiquated launch. This sported a rough canvas covering on thin wooden poles, as protection from the heat of the sun, fixed over the few rows of wooden benches it offered upon which to sit for the journey to the ship’s anchorage out in the bay. There followed an undignified scramble as everyone tried to be amongst the first aboard in order to secure a seat.

With much blue smoke and loud popping noises from the exhaust, the engine of the launch burst into life, lines were cast off with a great deal of shouting and gesticulation, there was one final thud against the jetty, that almost resulted in those clinging to the gunwale, or other handholds, being deposited in the rather scummy and oily water around the jetty, then the boat surged forward into the deep blue chop of the bay, sending spray splashing back over the bow, to wet we cramped and reeling passengers. In the distance, remote and rather lordly, surrounded by barges and other launches of varying kinds, and with a thin drift of smoke emanating from her brightly coloured funnel, lay the SS Ionia.

There can be no more impressive way to approach a ship than from a small launch, since no matter the size or age of the vessel toward which you are headed, it will tower over you and look far larger than it really is. In this instance, as the launch got closer to her, the Ionia looked big. I ignored the dents and bumps which decorated her hull, indicating fairly poor handling and seamanship at times and the rust which penetrated the paint on that hull in many places as I gazed at her, for with the sun shining on her, surrounded by the deep blue of the late afternoon sea and sky, her white superstructure gleamed and she looked every inch a ship with purpose and the confidence borne of many years hard, honest service.

She was a hive of activity, booms working, cargo being lifted aboard, and crew members scurrying about the decks, or hanging over the side in bosun’s chairs trying to cover up some of the more obvious rust spots. Approaching yet closer, it was possible to appreciate her lines, from the slightly raked stem to the neat counter stern. Her tall, partially cowl topped, funnel shone with new paint, its yellow colour, with a narrow royal blue band three quarters of the way up, plus the black top section testifying to her ownership. The superstructure was enclosed and glazed forward but partially open at the sides and the white of this reached down to bridge deck level where it extended from bow to stern. Her hull was pale grey above the boot topping at the water line, which was a dark red.

The launch in a final flurry of spray, swung alongside the companionway which hung down the starboard side of the ship, where it heaved in the swell, whilst we passengers jumped, or were dragged by members of the ship’s crew, onto this to begin our climb up to the open sided promenade deck. This, when reached, was bright with sunshine, yet shady, laid with a grey marbled linoleum strip over the teak decking. Dark varnished doors gave onto the deck from the accommodation, the main rooms of which were lit by square, aluminium framed windows, whilst other areas sported large brass portholes. Signs in French and Greek hung from the deckhead indicating the position on the deck above of the lifeboats and a few varnished wooden seats were ranged against the white painted bulkhead. At a table set up at the head of the companionway sat the ship’s purser, who was busily engaged in checking passenger’s tickets and sending them off with stewards to their respective cabins. Luggage had been consigned to a second launch and was being loaded aboard onto an after deck area from this by one of the cargo booms.

Having handed over my passport and ticket to the purser, as a first class passenger I followed the Chief Steward, to whom I had been passed, as he led me through a pair of varnished doors from the open promenade, into the cool and comparatively dark, entrance hall of the accommodation. Black and white check linoleum graced the floor, there was a wealth of varnished wood panelling on the bulkheads and a palm-like house plant decorated one corner of the hall. Descending a twin staircase to the main deck we reached, by way of a lobby, the long cream painted corridors off which were situated the first class cabins. These were mostly arranged with two or three berths and the outer ones each had small rectangular shaped windows instead of portholes. There was a wash basin in each cabin but showers, baths and toilets were all situated in a communal block amidships. These ablutions were, as I later discovered, almost directly adjacent to the boiler uptake and incredibly hot and airless. My own cabin was sparsely but adequately furnished and on the bed was a light coverlet which bore the company insignia.

Exploration of the 1st Class accommodation revealed a large lounge on the upper deck facing forward, simply furnished with sofas, Lloyd loom chairs a couple of writing desks and linoleum flooring; there was a smaller but more attractive reading room beneath this on the promenade deck and amidships on this same deck a narrow Tudor style wood panelled bar running the width of the deckhouse. Forward, below the main deck, was a large, panelled dining saloon, which was easily the most spacious of the public rooms on the ship. All the accommodation was spotlessly clean and provided comfortable surroundings for the voyage. The deck areas, including the boat deck, were kept well washed and scrubbed and on the upper levels were supplied with an assortment of deckchairs.

The Tourist ‘A’ class accommodation was situated in the poop, comprising two comfortable public rooms, a saloon and a dining room, plus a variety of somewhat plain and rather airless cabins on the lower decks, berthing from 4 passengers upward. Tourist ‘B’ in the forecastle, which was decidedly Spartan, apart from providing a big cafeteria style general saloon, mostly comprised dormitory style accommodation.

Although boarding of passengers was soon completed, loading of the cargo continued for most of the afternoon and was fascinating to observe as the holds gradually filled with a variety of sacks, boxes and other containers. Cars and trucks for transport were amongst the last items to come aboard, being secured on deck aft. At last the hatch covers were put into place with tarpaulins over them, the shouts and yells which had accompanied the loading died away and with a dark, velvet evening falling, all became peaceful. Later, as I strolled on the promenade deck I heard, the ship’s departure announced at 7pm; she gave three long, reverberating blasts on her siren and then with hardly any vibration the screw began to turn as the Ionia moved quietly and placidly out into Limassol Bay, leaving the lights of the town behind to twinkle over the black waters, under a heavily star studded sky. Dinner was served at eight o’clock, the dining room looking most attractive under soft lights, the white linen covered tables laid with silver cutlery, fresh flowers and a variety of wine glasses at each setting. The food, comprising a total of eight assorted courses, was plentiful, wholesome and simple in Greek style with fresh salad as a side serving to the main course. Thick, rich Turkish coffee and liqueurs served in the lounge finished off the meal. A calm, restful night at sea followed.

Early next morning as the Ioniaglided over a glassily smooth undulating swell, the mountains of the Lebanese coast came hazily into view with the ship’s approach to Beirut. By breakfast time she was running off the port, as a variety of small craft sailed out, their brown skinned Arab crewmen crowding their decks to wave at the Ionia and her passengers as they passed. One of these approached far too close to the Ionia sailing almost under her bows causing the Captain to order Ionia’s engines to go astern to prevent a collision, and for her then to be stopped in the water. As a result he appeared suddenly on the bridge wing from where he shouted abuse at those on the smaller vessel, who were clearly quite unconcerned. From on shore, meanwhile, the distant sound of a muezzin calling the faithful to prayer drifted across the water, whilst the air was filled with the myriad scents of the hot, dry land and the city. Ioniaslowly got underway again and moved gently over the flat calm toward the harbour entrance. Shortly a small pilot boat appeared headed for her bow and as it bumped alongside, the pilot jumped onto the Jacob’s ladder which had been hung over the side. With the ship still moving slowly ahead, the pilot scrambled up to the deck, then continued on up to the ship’s bridge.

Gradually the Ionia slid between the breakwater’s arms, turned and approached the jetties at the heart of the port, all of which were filled with a variety of ships, ranging from small coasting vessels, through cargo ships of various ages and sizes, to the gleaming white passenger ship Achilleus of Olympic Cruises. Ioniacame alongside a section of quay a short distance from the latter, making a strong contrast, with her dated appearance, to the sleek modern lines of the Achilleus. As the way fell off the ship and the heat and noise of the city surrounded her, she edged gently in toward the quay, ropes and hawsers were thrown to the waiting stevedores and she was brought carefully alongside; using the power of her own winches to pull herself in once the hawsers had been looped over the shoreside bollards. The companion ladder rattled down the side of the ship to allow the pilot to disembark and Ionia had arrived.

Ahead lay two hot sunny days in which to enjoy the heady pleasures of 1960’s Beirut, with it’s bazaars, souks, mosques, varied shopping, luxury hotels, lovely Corniche and exciting, slightly mysterious atmosphere. The various nightclubs, as well as the Casino du Liban, also had their attractions in the evenings. In due course, when they returned to the Ionia each night poorer in the pocket but satisfied, and before retiring below, passengers could enjoy the spectacle of the numerous floodlit ships in the port, which were visible from her upper decks,.

On the day of her departure from Beirut there was much activity on the quayside as, with her cargo hatches once again open, Ionia had unloaded cargo, and was now taking more on board. Equally did she take aboard a large number of passengers into the Tourist B class section of the ship, all of whom were well laden with their personal goods and chattels. No smiling, white jacketed stewards were allotted to take them to their berths and they were left to find their own way. Amongst them was a troupe of ladies of interesting aspect who, it was said, were performers from one of the city’s seedier nightclubs, en route to pastures new in Cairo. The vociferous exchanges between these ladies and a number of lounging dock workers who observed their arrival on board was illuminating, needing no knowledge of the language to understand, as the girls flounced across the fore deck to disappear into the depths of the accommodation under the forecastle.

As morning stretched into afternoon the Captain, clearly becoming impatient with the slow progress of loading the cargo, appeared on the starboard bridge wing, peaked cap askew, from where he called out orders to the other officers supervising the work. His intervention appeared to have no effect on the speed of operations, which continued in the normally accepted way in Middle Eastern countries, very slowly. At last, however, all was as it should be, with the hatches once more secured, the last dock worker had disappeared down onto the quayside and the ship was once more ready to sail.

Suddenly a great hubbub broke out as from one of the dockside buildings poured a large crowd, turbanned, fezzed or veiled, who stampeded toward the Ionia waving their arms, crying and wailing. This was a signal to the horde of tourist passengers that had earlier embarked, who now came toppling out from below onto the Ionia’s decks, equally emotive as the people on the quay. Thus, in a rather dramatic frenzy of wailing and weeping, with the Captain once more standing on the starboard wing of his bridge, his cap still askew, the Ionia departed Beirut in mid afternoon bound for Port Said.

Out of sight of the brown, sun dried land, surrounded by her element, the Ioniabegan to feel the deep movement of the sea. The heavy swell she encountered was still glassy smooth but built gradually until by the evening it had developed into a long sweeping motion which had the ship’s bows lifting high out of the water as each swell passed beneath them, a long slow plunge into the trough following, before the next swell lifted her again. This wild yet oily pitching motion ensured only a thin gathering for dinner in the dining saloon and a number of passengers hurriedly left their tables after only partially eating their meals. The somewhat under employed stewards lounging about the room, smiled at each other knowingly with each departure. On deck the night was beautiful, the black void of the sky was imprinted with a million brilliant stars and the moon shone silvery across the swell of the sea, throwing deep shadows between the troughs. The sound of the ship’s wake as she slowly sailed south westward varied from a gentle swish to a deep roar, as she alternately rode the crests and troughs of the waves. I enjoyed a last round of drinks in the bar before a final night of being rocked to sleep by the ship’s motion.

On awakening in the morning a look through my cabin window revealed that Ionia was approaching the Egyptian coast in a thin morning mist. She hove to some distance from the shore to await the pilot and once he was aboard headed into the busy harbour at Port Said. An early convoy of ships which was to pass through the Suez Canal was mustered nearby and around the Ionia there was a buzz of activity with dozens of small boats alongside, all full of vociferous, smiling Egyptians, many offering a vast array of wares for sale, their long tunics and variety of headgear adding to the colour of the scene; amongst the throng of these who had made their way onto the promenade deck I came across a ‘gully gully’ man demonstrating his abilities at magic tricks. To add to the hubbub there was a constant stream of porters and workers from the port going up and down the companion ladder to the boats below. In the distance the domed buildings of the Suez Canal control centre could be seen shimmering in a dusty heat haze.

After breakfast, there began the lengthy procedure of proving to the unsmiling emigration officials of Gamal Abdul Nasser’s regime that the visa in my passport was genuine and valid and that I really was only visiting the country as a tourist and not planning to enter it for some ulterior reason. For this procedure all the passengers were herded into a long queue stretching from the dining saloon, across the lobby and up the stairs to the lounge. When eventually I had been given clearance, it was then necessary to find and identify my luggage from the enormous heap on deck and commandeer a porter in exchange for a handful of coinage. After that I negotiated the steep companion ladder down into one of the boats bumping and bouncing around the ship’s hull. Safely into this, and with my luggage piled into the boat around me, it was time to bid farewell to the Ionia, her antiquated, yet attractive, lines diminishing and fading into the dusty haze, as the small boat carrying me headed away from her toward the shore and the awaiting wonders to be revealed in the ancient land of Egypt.

More detail »

S.S. Digby in World War One

S.S. Digby in World War One

SS Digby in World War One

A War in Two Navies

The S.S. Digby, 3,966grt, 350ft long, was launched from Irvine’s shipyard in Hartlepool on the 28th of December 1912. She would then have undergone the process known as ‘fitting out’, where her internal spaces were filled with equipment and furniture, engines, generators and all the things necessary to complete the ship. Then would come Sea Trials – engines would be tested as would navigating equipment. She had Triple Expansion Steam Engines built by Richardsons Westgarth Ltd., at their Middleton engineering works. Digby was capable of cruising at 12.5 knots, and used 42 tons of coal per day. She was completed in April 1913, and in common with other merchant ships of this time, her frame would have been strengthened, so that in times of war she could have guns mounted on her deck.

As a merchant ship she was unusual, for this era, in having a side loading door so that she could load some of her holds without the use of a large crane. She had 4 holds and was equipped with 7 watertight bulkheads. Her owners were Furness, Withy & Company Limited and she was intended for the Liverpool – St John’s Newfoundland (Canada) run, to carry cargo between Canada and Britain and immigrants, businessmen and employees travelling as part of their contract as the bulk of her passengers. The passage below is from a document intended for Genealogical Research and is a composite of newspaper clippings dated 1914.

S.S. Digby, Capt. Trinnick, reached port at 11 a.m. on Friday, after a run of 13 days from Liverpool. Leaving on Saturday, April 25th, she met with moderate weather, and made excellent time up to the 2nd inst., when heavy ice was run into about 170 miles E.N.E. of port. Dense fog then set in, and little headway could be made, the engines having to be stopped repeatedly. In order to escape the floe, the ship was headed south, but did not get around it till the Virgins had been reached. After much difficulty she made Cape Race at 3.30 p.m. on Thursday, but coming down the shore again met the floe, and ran off to sea during the night, working slowly in at the hour mentioned. Not until she reached the pier was the ship clear of the ice, as several small growlers had to be towed out of the way to allow her to berth. She brought 500 tons of cargo, a large mail, and as passengers C.P. Ayre, A.E. Hickman, J. and Mrs. Henderson in saloon, and Miss Dingle, H. Warby, J. Dolman, F. Smeaton, J. Facine and G. Galvin in second cabin.

With the approach of WW1 in 1914 the Admiralty chartered a number of merchant ships including the S.S. Digby to enforce their blockade of Germany. She was armed with 5x6in guns and 2x6pdr guns and became part of the 10th Cruiser Squadron, as HMS Digby, under Admiral De Chair. She appears to have operated mainly out of Glasgow, Queens Dock, where coaling facilities were available as well as regular berths. Some of her hold space would have been converted to coal bunkers as she needed more fuel to be able to patrol effectively.

HMS Digby’s Patrol Area seems to have been quite far north, including Iceland, her duties were to stop ships and check that they were not carrying cargo related to the German war effort or personnel returning to serve in the German forces. Her first log entries show her taking on coal, moving berths and painting, and re-ordering the ship to accommodate the wartime layout. There are also pieces of equipment coming aboard such as ammunition on March 10th and a sounding machine on March 11th (for submarine detection it is presumed).

The ship’s crew practiced drills with the ship’s boats, patrolling and doing the ‘Abandon Ship’ practice – vital for new crew members! On patrol they seem to have sighted the periscope of submarines and pursued them as well as meeting other ships from the 10th Cruiser Squadron and exchanging signals.

Having a boat on patrol at night could prevent sabotage, especially in a foreign port, as well as the possibility of theft from ships stores. During a patrol they would intercept a ship and if, in their opinion, it contained goods or personnel that were forbidden they would proceed to a nearby port under a prize crew. If the vessel was German or from one of Germany’s allies the vessel herself would become a prize and be sold, or used by the Navy.

The ship’s crew seem to be always practicing drills for boats crews (boarding parties etc.), guns crews and also the searchlight crew. They regularly meet trawlers from Denmark, Sweden and Norway which they also search in case they are blockade runners. Ports visited include Reykjavik in Iceland and Torshavn in the Faroe Islands, British Consuls as well as local naval personnel would come aboard. Information could be exchanged with friendly neutrals and valuable contacts made as well as refuelling and loading stores. One piece of unloading is interesting, 2 boxes of cordite – the charge used to propel the shell – are unloaded for special examination; one type of cordite could become unstable (liable to explode) if stored for too long.

On 6th April HMS Digby was in the Mersey heading for Liverpool Docks, two Lieutenants in the RNR (Royal Naval Reserve) joined the ship there as well as an Engineer Lieutenant RNR. There were other comings and goings of ship’s crew and it is probable that this was one reason for the Digby being in Liverpool.

The Digby, on the way out of Liverpool, seems to have suffered from engine room defects – probably caused by the constant patrolling – and has to go to Belfast for repairs. At Belfast they seem to have acquired a 3rd Engineer and a visit by a Chief Gunner, as well as having the Boiler Room Fan repaired. The fans were necessary to provide sufficient air for the engines and boilers to work. Simply opening 'doors and windows' wouldn't let in enough air so fans (sometimes referred to as forced-draught fans) or 'blowers' were used to force air into the engine/boiler rooms.

She seems to have left Belfast around 25th April and gone to resume her patrol in the North. On the 26th of April she is in Reykjavik, Iceland, with the Consul visiting, they also entertain the Captain of a Danish gunboat.

On the 2nd of May the log records the Captain reading the ‘Articles of War’ to the crew after Divisions (a Parade of crew members) and Prayers (a Sunday, when all were present). These set out punishments and the standards of behaviour required by RN crews in wartime at this period. All members of the crew were required to be familiar with them and so they were read to the crew by an officer to ensure this.

An incident on the 3rd of June 1915 illustrates the work HMS Digby undertakes. The Swedish Trawler ‘Violette’ is boarded and as she is found to be a suspected blockade runner, she is given an armed guard and sent to the Harbour in Kirkwall for further examination. Shipboard life goes on as usual, as well as the practices for boats crews, guns crews and searchlight crews they are paid and issued with soap and tobacco. The crew are kept busy cleaning the ship and maintaining her guns and boats. The Digby also seems to exchange signals (using flags) with many other ships of the 10th Cruiser Squadron either inbound or outbound to their patrol areas.

While in dock at Glasgow a couple of incidents occur, in one a marine loses his bayonet overboard (he would probably have to pay for this out of his wages). The other thing that happened was a man fell overboard from another ship (HMS Ambrose) and HMS Digby sent a Petty Officer to report to HMS Ambrose that they had recovered him, and he was injured.

At sea again, around 30th June, the Digby has come across wreckage and sinks some items by rifle fire and others by using her guns. She also picks up a quantity of bales of cotton, very useful for the manufacture of cordite, also they may have had numbers on which could identify the ship they were from.

On 25th November 1915 the HMS Digby became the French Auxiliary Cruiser ‘Artois’

Why did HMS Digby become the Auxiliary Cruiser Artois?

The Admiralty was advised by the American Ambassador that it would be better if American blockade runners were arrested by a French ship – less of an embarrassment (we hoped the Americans would help us in the war) than a British ship. The French agreed and, as they had no suitable ships, we lent them two, one of which was HMS Digby which became the Artois. She was commissioned at the French Naval Base at Brest along with HMS Oropesa which became the Champagne.

The Artois was given as Captain, Paul Marie Gabriel Amédée De Marguerye, a distinguished French naval officer and sent north to rejoin the 10th Cruiser Squadron once again. She did not have the easiest of starts as she was expected to operate as the English crews did, and the French were not aware of the requirements of the job. With help from the Admiral and the officers of his Flagship, HMS Alsatian, the crew of the Artois got the hang of things and proceeded to operate the blockade as required.

They stood by a dismasted sailing vessel and, eventually, towed the vessel into Stornoway – to the great relief of all! Another incident that occurred was when the Artois was chased by a submarine which she eventually evaded. The Auxiliary Cruiser Artois continued the work of the blockade as she did in English Naval Service. She met and challenged other ships, exchanged greetings with her colleagues in the 10th Cruiser Squadron and avoided the German submarines which were a menace. These submarines, apart from sinking ships, were used to lay mines in the approaches to Britain and around British ports.

In 1917 the Artois was returned to British control and became the Royal Navy’s HMS Artois, the name was retained as there had been a ship of that name on the Royal Navy List in the 18th century. She is pictured in her ‘dazzle’ camouflage, this was designed to break up the silhouette of a ship and make her difficult to identify through binoculars or a telescope or, most importantly, the periscope of a submarine. Each camouflage arrangement was unique to the ship it was applied to.

The logs for HMS Artois are much more Royal Navy than the early logs of HMS Digby. On the 19th July ratings (seamen) arrive at the ship, berthed in Glasgow and the following day some marines arrive. Stores are loaded, including 32 cases of wines and spirits for the Wardroom (the wardroom is the officers eating and entertaining space aboard ship). Some absentee sailors from another ship report to HMS Artois and are sent on to the shore establishment for redeployment or return to their previous ship (or, if necessary, for punishment for being absent without leave). A RNLI absentee also reported, it can be assumed that HMS Artois was the only RN ship in the dock at that time and orders were to report to the nearest RN ship (even shore establishments were ‘ships’ in this sense). More ratings join the ship and the Officer of the Watch has to check a cabin where confidential items (presumably code books) are and post a sentry – essential whilst in dock. Medical stores come aboard, the ship would have sick berth attendants, a surgeon, and only a small sickbay, a sick fireman is discharged to hospital.

On 5th August HMS Artois heads down to Greenock with the Pilot aboard having received the up to date code flags. The ship’s cutter then lands the paymaster and the postman, having both discharged their duties. The cutter, the ship’s motor boat, then returns to the ship. The next day they weigh anchor and proceed to sea, they follow a zig zag course to confuse submarines. HMS Artois then joins up with HMS Motagua and they continue until the Motagua leaves for her patrol area. The Artois then continues with the two sloops ‘Buttercup’ and ‘Primrose’ until they also leave.

On the 9th of August HMS Artois has two torpedoes launched at her, they pass, one at the stern and one at the bow (the dazzle camouflage has done it’s job!), they then drop a depth charge which fails to explode unfortunately. Later on in the day they pass a lifeboat which was empty, and a raft with no sign of life, sad reminders of a ship which a submarine had probably sunk – possibly the one that had tried to sink them.

HMS Artois joins HMS Patia and both ships are on a zig zag course, the weather worsens and waves come over the ship’s bow. They encounter two Danish sailing ships and challenge and examine the cargo and crew. HMS Patuca is sighted and flag signals are exchanged. The next day they sight two patrol trawlers and the following day the American steam ship S.S. Ida which is allowed to continue her journey. As well as the Ida they also stop and board the Belgian relief ship ‘Adolph Deppe’ and the ‘Herato’. A busy day for HMS Artois!

If a ship is flying the correct code flag for the day she is not intercepted, though she is recorded in the log as being seen. HMS Artois has quite a few entries showing this, the Artois then sets course for a meeting with the flagship, HMS Alsatian. The Admiral comes aboard for a meeting and then leaves to return to HMS Alsatian. The following day, whilst on patrol the Engineer examines the steering gear control and reports it as ok, possibly the ship had been slow at responding to course changes, they were zig zagging a lot to avoid submarines. They then run into bad weather with heavy swells and the ship is pitching a lot and ‘falling off’ (being pushed off course by the strength of the waves) and having to be manually brought back on course.

HMS Alsatian, the flagship, is sighted and a boat is received from her, probably carrying orders the boat soon returns to the flagship. Next day the Artois has some trouble with her engines and has to stop for repairs. She continues her patrol intercepting ships of various sizes and sorts (as well as nationalities). On 30th August HMS Artois has more trouble with her engines, this time a connecting rod is overheating and they have to reduce speed. She is then on the return leg of her patrol on the way back towards Glasgow.

On Friday 7th of September HMS Artois is back at Queens Dock in Glasgow, the sailors are employed in cleaning and painting the ship and repairing the windlass (used for hauling the anchor up). The men are paid (monthly pay parade) and some dockyard workers are aboard. These workers appear to be cleaning out water tanks and holds. The following day the ship is shifted 10 yards (probably to accommodate another ship). Then on the following day HMS Artois is shifted again to allow the removal of her P2 5inch guns. The sailors are then employed with refitting as a consequence. Four new ratings (sailors) join the ship and she is moved to the coaling wharf to take on coal. They spend the next two days taking on and stowing ammunition, one sailor is taken off to hospital. Painters, fitters and shipwrights are all on board working on the ship.

The log refers to a funeral party but does not say if the party of men dispatched was attending the funeral of a shipmate, or providing an RN presence at the funeral of someone else. They take on more coal and then shift the ship for the removal of the P1 6inch gun. On the 17th September they put the clocks back and the following day they leave Princes Dock. They anchor at Lamlash and the Captain goes ashore and returns, the sailors are fusing shells (the fuse dictates how long it is before the shell explodes). On the 21st HMS Artois receives orders and leaves Lamlash.

It seems that HMS Artois was employed in escorting a convoy from Tory Island (County Donegal) until they were in safer waters off the Ayrshire coast at Turnberry Point. HMS Artois then resumes her patrol routine, the sea seems to have been particularly rough and the ship is moving about. Ships are challenged and replies received including from the flagship HMS Alsatian. The sailors are employed securing the rafts so that the heavy seas do not wash them overboard. On the 26th HMS Artois actually fires a round across the bow of a steamer to get her to stop and be inspected, usually they stop when challenged but obviously this ship was trying to get away with it.

On the 5th of October HMS Artois is inspecting trawlers; she is also getting in some gunnery practice at a dummy submarine target. HMS Artois is also zig zagging to avoid submarines meanwhile repairing her wireless aerial. They also practice shooting at a target with their rifles, a few days later they have pistol practice as well, for the boarding crews only.

By the 12th of October they are anchored in Loch Ewe, taking aboard coal from two collier barges. HMS Artois is under way again on the 14th, heading out to sea, apparently with a convoy, as HMS Artois is keeping station (following at a prescribed distance) on another ship. Some of the sailors are refitting a magazine – possibly to turn it back into a cargo hold. They reach Sydney, Nova Scotia, Canada on Wednesday 24th of October and anchor in the harbour there.

HMS Artois takes on coal for her return journey, there is no mention of loading cargo, though there could have been some loaded as the UK was in need of food provisions at this time, as well as military equipment and raw materials. Water is also taken on at this time via water boats, sailors return from shore leave (liberty men). The next day a party is landed to play football and a company of Marines for small arms drill and a Route March. On the 28th October some signal ratings join the ship, these will be dispersed throughout the convoy to interpret signals and return answers. The first lot of sailors and signalmen are sent to the ‘S.S. Lake Michigan’, the convoy gets under way the following day, lining up by columns.

HMS Artois is on station ahead of the SS Lake Michigan and the convoy is doing a zig zag pattern to confuse submarines. The crew practice various drills including gun drills, the Midshipmen (Trainee Officers) are apparently allocated to the 6 pounder gun. SS Rapello (a merchant ship in the convoy) has to reduce speed to mend the steering gear and the convoy reduces speed to match hers.

On November 2nd, more practice at gunnery and signalling is done and the decks are scrubbed. HMS Artois then takes the position in the convoy that was occupied by the SS Lake Michigan, the weather is getting worse. The ship is rolling about and the weather is rainy and windy, the ship is darkened at night so that no light shows to guide a submarine to the convoy.

Inishtrahull Lighthouse in County Donegal is sighted on 9th November and the convoy puts their clocks to GMT (Greenwich Mean Time). The ships are now travelling in line ahead. The convoy is ordered to follow a destroyer and HMS Artois heads for Queens Dock where she ties up on the 11th November.

HMS Artois then commences to load up with coal, 462 tons in total. One of the engine room crew was placed under arrest (he was released the following day). The Captain left the ship, possibly to receive orders or perhaps to call on the officers of another ship (or shore establishment) or even to have some leave. On the 14th and 15th of November the ship’s stability is tested and adjusted so that she sits level in the water, excess stability weights are stowed on shore. 5 more sailors arrived on the 17th and one of the groups of sailors that had been on leave returned. On the 18th the Captain returns and the ship finishes loading up with fresh water.

HMS Artois leaves Glasgow for Greenock where they receive post and the sailors are issued their soap and tobacco rations, some officers come aboard, then on to Lamlash, a convoy assembly point. The Captain and the Captain of the Port leave the ship – probably for meetings about the convoy. HMS Artois leaves for Belfast Lough with the convoy on 23rd November, two officers are cautioned for remaining absent without leave at Lamlash. After passing Inishtrahull Lighthouse 6ft of water is discovered in no 1 hold, this is checked every hour, and is increasing then the electric pump breaks down and they decide to head for Lough Swilly.

HMS Artois then is told to leave for Belfast to get the problem with No 1 hold fixed. On the 30th of November at 9:55 am HMS Artois ties up in Belfast at Alexandra Jetty. On the 4th of December the coxswain reports that the motor boat had been on fire, this may have been sabotage or just carelessness, a leading seaman has been taken to hospital. The log reports that the seamen were ‘told off’ this is not, as we would expect, a stern word from the officer of the day but a way of saying they were allocated to particular tasks. By 10th December HMS Artois is in the Thomson Dry Dock ready to be repaired, her ammunition has been taken ashore previously to prevent accidents.

Two absentees from the crew rejoin the ship from Liverpool. Then HMS Artois leaves dry dock on the 14th December and ties up at the jetty. She loads meat and ammunition, on the 17th she is shifted to another position to load some barrels (the ‘containers’ of the day) into No 1 hold. The Quartermaster and Corporal of the Gangway (access to the ship) were absent from their posts when the Captain returned aboard – they would have definitely been punished for this offence. HMS Artois is shifted, with a Pilot aboard (the Pilot knows his part of the coast extremely well and navigates the ship during this time), to Belfast Lough where she anchors. HMS Artois then sets sail on the 19th December for Glasgow, Queens Dock which she reaches at 2:25 pm tying up at Berth 7 (a Berth is an allocated space for a ship at the dockside).

A seaman joins the ship as a storekeeper, 10 stokers (men employed to put the coal in the boilers) also come on board on 22nd December, and the ship is shifted to berth 18. The sailors are employed landing the ammunition on the 23rd December, it being all out by the end of the day. On the 24th December an escort is provided to fetch a prisoner and escort and prisoner return to the ship.

On December 25th (Christmas Day) the crew are landed to attend Church both RC (Roman Catholic) and CofE (Church of England – Scottish Episcopal Church). Seamen are given liberty (leave) after lunch at 12:00 usually each ‘watch’ (named Port and Starboard after the sides of the ship) gets liberty separately. December 27th HMS Artois is shifted to Berth 8 in Princes Dock, more men are given liberty. Dockyard men are aboard and some sailors are returning from long leave. The last log entry records men getting liberty and others cleaning the ship.

The logs for 1917 – January 1919 are not online, though one for September 1918 is in the National Archives. It could be assumed that HMS Artois either returned to Blockade duties with the 10th Cruiser Squadron or, more likely, continued to escort convoys across the Atlantic, or elsewhere. There is no mention in the logs of all her guns being removed. As some First World War Hospital Ships were sunk towards the end of the war, she may have been used in this capacity, or even as a Troop Ship. There exist some Entertainment Programmes for HMS Artois, dated 4th October 1918, 13th October 1918 and a Grand Concert called ‘Somewhere at Sea’ on the 17th October 1918. She was then taken out of service (laid up) and eventually was returned to her owners (Furness Withy) in 1919.

More detail » Baltrover

Baltrover

Created by unknown

Donated by Mr. Derek Longly

Created by unknown

Donated by Mr. Derek LonglyThe Baltrover in the late-1930s to mid-1940s. She was originally built as the Digby.

More detail »