Hartlepool Sports & Leisure

Hartlepool Sports & Leisure

- Cinemas, Theatres & Dance Halls

- Musicians & Bands

- At the Seaside

- Parks & Gardens

- Caravans & Camping

- Sport

Hartlepool Transport

Hartlepool Transport

- Airfields & Aircraft

- Railways

- Buses & Commercial Vehicles

- Cars & Motorbikes

- The Ferry

- Horse drawn vehicles

A Potted History Of Hartlepool

A Potted History Of Hartlepool

- Unidentified images

- Sources of information

- Archaeology & Ancient History

- Local Government

- Printed Notices & Papers

- Aerial Photographs

- Events, Visitors & VIPs

Hartlepool Trade & Industry

Hartlepool Trade & Industry

- Trade Fairs

- Local businesses

- Iron & Steel

- Shops & Shopping

- Fishing industry

- Farming & Rural Landscape

- Pubs, Clubs & Hotels

Hartlepool Health & Education

Hartlepool Health & Education

- Schools & Colleges

- Hospitals & Workhouses

- Public Health & Utilities

- Ambulance Service

- Police Services

- Fire Services

Hartlepool People

Hartlepool People

Hartlepool Places

Hartlepool Places

Hartlepool at War

Hartlepool at War

Hartlepool Ships & Shipping

Hartlepool Ships & Shipping

Pilots and Boats

Details about Pilots And Boats

The people and boats of the Hartlepool Pilots Association.

Location

Related items :

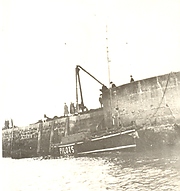

"A. G. Murrell" (1) putting to sea

"A. G. Murrell" (1) putting to sea

Donated by Mr. Bert Spaldin

Donated by Mr. Bert SpaldinDated 1955

The Pilot Boat A.G. Murrell (2), putting out to sea with the coaster J.H. Jonas, to disembark her Pilot. 1955.

More detail » "A. G. Murrell" (2) returning to station

"A. G. Murrell" (2) returning to station

Donated by Mr. Bert Spaldin

Donated by Mr. Bert SpaldinDated 1960

The Pilot Boat A.G. Murrell (the second of that name), entering harbour after attending to a ship, sometime in 1960.

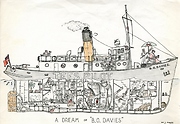

More detail » A Dream of B.O. Davies

A Dream of B.O. Davies

Created by Sam Roberts

Donated by Mr. Stan Lithgo

Created by Sam Roberts

Donated by Mr. Stan LithgoAn excellent cartoon of the Pilot Boat B.O. Davies by Sam Roberts.

More detail » A General History of Pilotage in Hartlepool

A General History of Pilotage in Hartlepool

What is a Pilot?

A pilot is someone who goes aboard a ship to guide it safely into or out of a harbour. They are usually local people, with a detailed knowledge of their particular area of water.

Pilots played an important part in the development of the Hartlepools. A major part of the towns’ income in the second part of the 19th century came from the ports. Ships had to be able to get merchandise to the docks, and back out again, as safely and as quickly as possible. The seas around the coast are dangerous, with many hidden rocks and sandbanks. Without the help of the pilots to guide them, many ships could have got into difficulty, and lives and cargo lost.

Trinity House and the Pilots

Trinity House is a maritime organisation involved in the safety of shipping and the welfare of mariners. It is runs the lighthouses and navigational aids in England and Wales. Until 1988, it was also responsible for pilots.

Trinity House has its origins in the 13th century, when a religious organisation called the Order of St Trinitas looked after needy sailors. They provided shelter for shipwrecked seamen, and those who were unable to take care of themselves due to accident or illness. They also provided almshouses (rent-free housing) for the families of men lost at sea. The seamen involved in the organisation gradually formed a series of Guilds around the country. These gave navigational advice to shipmasters in their area, and encouraged the development of the ports. The Guilds kept their religious origins, and the members were known as Bretheren. The first Guild to be formed in the north east was in 1300. It was originally at Berwick-upon-Tweed, near the border with Scotland, but soon moved to Newcastle. It financed itself by collecting fees from vessels mooring in the River Tyne to load and unload cargo.

On 4th January 1492 the Order of St Trinitas changed its name to the “Society of Masters and Mariners”, commonly known as Trinity House. It was based in London, but had branches at Scarborough, Hull, Dover, Leith and Dundee, as well as Newcastle. By the early 17th century, Trinity House’s duties were:

- To collect a fee (duty) on all cargoes coming in to port

- To charge a fee to every ship coming in to port, the money to be spent on maintaining lighthouses.

- To appoint pilots

- To set the fee a pilot could charge for his services

- To provide buoy markers for safe navigation

- To settle mariner’s disputes

- To support the poor associated with the House

Originally, Trinity House, Newcastle had only been responsible for the River Tyne and the sea approaching it. In 1606, however, the responsibilities of the House were spread to cover ninety miles (145km) of the coast, from Holy Island in the north to Whitby in the south.

In 1808 Parliament passed the Maritime Pilotage Act. This meant that all pilots had to be registered with Trinity House. If they met the standards laid down by Trinity House, they were issued with a license. Licenses were only valid for a particular area of water. For example, some pilots were licensed to take ships into the River Tees, but not back out.

The Ruler of Pilots

By the early 19th century, Trinity House, Newcastle, was responsible for ninety miles (145 km) of coastline, making it difficult to govern the more distant ports. This was solved by appointing a Ruler of Pilots (also known as a Pilot Master) for these ports. The first Ruler of Pilots for Hartlepool and the River Tees was appointed in 1811. His name was Anthony Pounder, and he had a house and office at Southgate, Hartlepool. It was the Ruler’s responsibility to make sure a pilot met any vessel which requested their services. He had to keep a register of pilots, and ensure that only licensed pilots were used. He was entitled to a portion of the pilots’ earnings, and also to part of the annual fee each pilot had to pay to renew his license.

In 1846 a group of nine Sub-Commissioners was formed to help the Ruler govern the Hartlepool pilots. They held their meetings in Hartlepool, although they were still answerable to Trinity House, Newcastle. The new committee was needed as the number of pilots had increased during the 19th century. The north east ports had become much busier due to the Industrial Revolution. Coal from the mines in County Durham had to be shipped around the country to power the new machinery. West Hartlepool developed its own port, and its first dock opened in 1847. This dock also had its own pilots.

Claiming Independence

Many pilots and shipowners were unhappy about being governed by Trinity House. They felt that they should not be run by an organisation which was thirty miles away. They also felt that any profits made should go directly into the local port, not to Trinity House. In 1864 the Hartlepool Pilotage Commissioners were formed to take control of the local pilots. Their name was changed to the Hartlepools Pilotage Authority in 1922. Trinity House’s duties at Stockton, Middlesbrough and Redcar were taken over by the Tees Pilotage Commission on 1st May 1882. Normally at this time pilots were allowed only one license, to work a particular area. Unusually, local pilots were allowed to hold licences for both the Hartlepools and the Tees until the end of the First World War (1918). At this point they had to choose which port to work, as they could no longer do both.

Pilotage services were re-organised in 1988, and the Tees and Hartlepool pilots were once again amalgamated. Today the service is run by the Tees and Hartlepool Port Authority, based at the Pilot Station at South Gare on the River Tees. All the pilots are now licensed for both ports.

Trinity House ceased operating pilots in 1988. Today, it is responsible for lighthouses, the safety, welfare and training of mariners, and Deep Sea pilots (pilots who stay on board a vessel the whole time it is trading in European waters).

How to become a Pilot

Each pilot had a license to work a particular stretch of water. In the early part of the 19th century, there were twenty-four pilots licensed for Hartlepool, and twelve of these also had a license for the River Tees. As the ports became busier, more pilots were needed. By 1851, there were seventy-nine pilots for Hartlepool, twelve of whom had licenses for the Tees.

Pilots in the mid-19th century were self-employed, but they were governed by Trinity House, Newcastle. Their licenses had to be renewed on 5th August every year. There were strict rules about who could have a license:

- Only relatives of qualified pilots could apply.

- An applicant had to have a good character.

- An applicant had to find an existing pilot willing to take him on as an apprentice.

- Once he had his license, the new pilot had to hire or buy a coble (a type of small boat the pilots used to row or sail out to meet incoming ships).

In addition, the applicant had to pass an exam:

- He had to show knowledge of the navigational marks, buoys and beacons in his district.

- He had to understand the local currents and how they were affected by sandbanks, rocks etc.

- He had to demonstrate the correct handling of sailing vessels under various conditions of sail and tide.

The apprenticeship to become a pilot lasted about five or six years. The number of licenses was limited, so even after qualifying a pilot might have to wait for an existing pilot to die or retire. If any pilots broke any of the Trinity House rules, or if they caused a ship in their care to be damaged, they were punished by having their license suspended or cancelled. The apprenticeship scheme lasted until the 1950s. After this, pilots were recruited from seamen with a Master Mariners certificate.

What's in a Name?

The earliest known licensed pilots for Hartlepool were William Coulson, Robert Johnson and William Hastings, who received their licenses in 1747. Because licenses were only granted to relatives of existing pilots, the same families were connected to piloting throughout many generations. In Hartlepool and Seaton, these were the families of Boagey, Pounder, Lithgo, Hunter, Harrison, Hodgson and Coulson. In the 1860s the rules were relaxed as more pilots were needed. From this point other families also became involved with piloting.

Looking for Work

The pilots charged a fee to every ship they brought in or out of harbour. The price depended on the size and tonnage of a vessel, and was calculated by the depth of the ship in the water. In 1851 the rate for Hartlepool was one shilling and three pence per foot in summer, and one shilling and sixpence per foot in winter. By today’s prices, this would be about £4- £5 per foot. Bad weather in winter would make the job harder, hence the higher charge. A portion of the fee was paid over to Trinity House.

A large part of a pilot’s time was spent in looking for ships to guide into harbour. They would often travel far out from shore in order to be the first to spot an incoming ship. They could be at sea for hours in open topped boats, with very little shelter from the wind, rain or cold. Once a likely ship was sighted, the pilots had to race one another to reach her first. Underhand tactics were sometimes used to gain an advantage. The boats (called cobles) were often sabotaged by rival pilots. This was done by puncturing the hull or damaging the sails or rudder. Sometimes a bucket was secretly slung under a boat, so that the drag would slow her down.

Once a pilot had reached a ship, he first had to make sure it was bound for his home port. Then the pilot would jump across from his boat to the other ship, and catch hold of a rope ladder to climb on board. This was difficult and dangerous. If the pilot jumped too soon, his coble could rise on a wave and knock him off the ladder. If he jumped too late, the coble would drop away underneath him, making him lose his grip on the ladder. If the pilot fell into the water his heavy clothes would drag him down, and he might drown.

Once aboard, the pilot would stay with the ship to guide her into harbour. His coble would either be towed behind the ship, or else sailed back by his apprentice. Once the ship was docked, the pilot would re-join his coble, and go back out looking for work.

Masters of ships often had “preferred” pilots in each port. This was a pilot they used regularly. They would notify their preferred pilot when the ship was due to arrive, and he would sail out to meet them. Getting the message to the pilot was difficult in the days before radio. Before the 19th century, messages were sent via other, faster, ships. As communications improved, a message could be sent by letter or by a system of signalling stations which had been set up around the coast. One pilot was known to use homing pigeons, which were released by an obliging lighthouse keeper when he recognised a passing ship.

The Cobles

The pilots’ boats were called “cobles”, and were similar to those used by the local fishermen. The coble is a kind of boat which is only found on the north east coast of England, and is still used as a fishing boat today. The design of the pilots’ coble differed depending on where it had been built. In the middle of the 19th century, Hartlepool boats were built by Jonathan Cambridge, in his yard overlooking the Fish Sands, and by the Pounder family. Hartlepool-built cobles were 27 to 28 feet (around 8.5m) long, 5 to 6 feet (1.5m) across, and about 2.5 to 3 feet (1m) deep. They were made from only ten planks of wood. This required great skill, but meant that there were fewer joints, so the boat was much stronger. This was important because the coble would get buffeted about when it was alongside a ship’s hull. At the beginning of the 19th century, they carried a two-man crew, but by the end of the century this had increased to three. The third person was an assistant to help row or sail the boat.

Each boat carried a spare rudder and two removable masts; a short one for bad weather, and a larger one for fine weather. In heavy seas, sacks of sand were used as ballast (a heavy weight to make the boat more stable). Pilot cobles could be recognised by their markings. They were always painted or tarred black, with their licence number and port identification letter on the side (bow). The identification letter for Hartlepool was an “H”. The boats all flew a red and white flag. Some pilots had two types of vessel, a coble and a boat. Boats were lighter, and handled better in fine weather. They were 18 ½ feet (5.5m) long. They had no mast, and were rowed by the pilot and his apprentice. When not in use, the boats and cobles could be landed on the beach, and dragged up above the high tide mark. At Hartlepool, they were tied up alongside the “Old” Pier, which became known as the Pilots Pier.

The boats and cobles became less practical by the end of the 19th century. Cargo ships changed from sail to steam-power, but the pilots kept their traditional vessels. They could not launch their cobles in bad weather, which cost the shipowners valuable time. In the early 1900s the pilots began to use steam cutters. These were larger boats powered by engines, which meant that they were not so much at the mercy of the wind or tide. The cutter would go out taking several pilots at a time. When a ship arrived, a pilot would be ferried over in a small boat. The cutter would also collect pilots who had been guiding outward-bound ships out of the harbour. When all the pilots had been collected or put on board ships, the cutter would go back to harbour to pick up another group.

Earning a Bit on the Side

How much a pilot earned depended on the number of ships he could guide in or out of the harbour. During quiet times, many pilots made extra money from fishing. In winter and spring they caught cod, haddock and whiting. At the end of the summer there were salmon, returning to the River Tees to spawn. Crabs and lobsters could be found among the rocks on the coast. The pilots also sold bait to passing Scottish fishing boats. These arrived in late summer every year, following shoals of migrating mackerel.

Other sources of income included gathering seaweed, which was sold to local farmers as a fertiliser. They also salvaged for wreckage washed up onto the beach. This might include rope, timbers and sails, tar, pitch, copper nails and oakum (a tarred rope fibre, used to waterproof seams in wooden ships). They also collected sea coal from the beach at Seaton Carew, which can be dried out and used as fuel. This is still done by many locals today.

What the Well-Dressed Pilot is Wearing

Pilots spent hours at sea in open boats, looking for business. They needed clothing which would keep them as warm and dry as possible. Pilots around the country wore different styles of dress, but pilots working the same stretch of water all wore similar clothes as a uniform. At the end of the 19th century a Hartlepool pilot would wear:

- thick woollen trousers

- a navy blue donkey jacket

- a thick woollen jersey called a gansey

- oilskins made from stiff calico (a thick cotton fabric) waterproofed with boiled linseed oil

- woollen or silk gloves inside leather gloves

- woollen stockings

- knee length leather boots (the soles were held on with wooden pegs, as nails would have rusted in the seawater)

- a sou’wester (waterproof hat) or a peaked cap.

Warm, waterproof clothing is just as important today. A modern pilot is issued with warm trousers and waterproof shoes. The most important item of clothing, however, is the coat. This has a life jacket built into it. If the pilot falls into the water, the life jacket inflates automatically. The coat is also fitted with a light, which can be seen by rescuers over a great distance.

Conclusion

Piloting is a highly skilled and dangerous job. The local pilots from the mid to the end of the 19th century had a particularly difficult time. The demand for coal meant a huge increase in the number of ships to carry it around the coast. Pilots were needed more than they ever had been before. But conditions at that time were very harsh. The boats and the equipment they used were basic, and there was very little regard for safety. Nevertheless, a pilot was a respected member of the community. There are families in the towns today who have been linked to piloting for generations. Without the pilots to navigate the ships into and out of the docks, the towns of Hartlepool and West Hartlepool would never have become the successful ports which they were at the end of the 19th century.

More detail » A.G. Murrell (4)

A.G. Murrell (4)

Created by unknown

Donated by Bert Spaldin

Created by unknown

Donated by Bert SpaldinPart of the Bert Spaldin collection

Un-dated image of the Pilot boat A.G. Murrell.

More detail » Assisting a tanker

Assisting a tanker

Donated by Mr. Bert Spaldin

Donated by Mr. Bert SpaldinThe Pilot Boat T.H. Tilly (second of that name), is seen alongside the tanker British Captain, off the entrance to the River Tyne sometime during the Second World War.

More detail » Blanchland - a general history

Blanchland - a general history

This 'Noticeboard' contains snippets of information about the ship drawn from a wide range of personal and documentary sources and is updated as and when new material is received:

From Mr. Stan Lithgo: "Went to Hartlepool on October 31st, 1961. Pilots from the Tees were often sent to nearby ports to save time picking up a Pilot in Tees Bay. In my case, the Blanchland was bound to drydock at Smith's Dock, South Bank. Derrick Southern (my cousin), was the Hartlepool Pilot. The ship was delayed by half an hour because the swing bridge was not opened on account of shift workers crossing. When clear, Derrick stayed on board, but when we reached Smith's it was too late to drydock.

When the Blanchland sailed from Smith's, the Pilot, W. Garthwaite (known as 'Big Bill'), was unable to disembark on account of north-easterly gales and heavy seas. The ship was bound for Dalhousie in Canada and was going north-about, so arrangements were made to land the Pilot by fishing boat at Scrabster in the Pentland Firth. Maybe some of Gray's personnel could have been on board?"

A “Casualties” listing in the January 1986 issue of Marine News states that Ionian Princess “which arrived at Inchon [South Korea] 20/8/85 with engine damage sustained during a voyage from Shekou [southern China] to Qinhuangdao [northern China] and has meantime been laid up there, has now been sold by the mortgagees to Chinese shipbreakers.”

More detail » Crew of "T. H. Tilly" (2)

Crew of "T. H. Tilly" (2)

Donated by Mr. Bert Spaldin

Donated by Mr. Bert SpaldinThe crew of the Pilot Boat T.H. Tilly (second of that name), circa 1935. The boat is laid up for her annual overhaul.

More detail » Disembarking from the Egton

Disembarking from the Egton

Donated by Mr. Bert Spaldin

Donated by Mr. Bert SpaldinDated 1986

1986. As the Egton (built in 1962 by Bartram & Sons, Sunderland), heads out to sea, the Pilot disembarks to the Pilot Boat Crofter.

More detail » Early steam powered Pilot Cutter

Early steam powered Pilot Cutter

Created by Francis Elsdon

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Created by Francis Elsdon

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServicePart of the Elsdon Collection collection

Early steam powered Pilot Cutter leaving Hartlepool

More detail » Hartlepool Pilots - circa 1935

Hartlepool Pilots - circa 1935

Donated by Mr. Bert Spaldin

Donated by Mr. Bert SpaldinDated 1935

A group of Hartlepool Piloits circa 1935.

More detail » Heading out to sea

Heading out to sea

Donated by Mr. Bert Spaldin

Donated by Mr. Bert SpaldinThe Pilot Boat T.H. Tilly (second of that name), heads slowly out to sea in 1926.

More detail » Launch of "T. H. Tilly" (1)

Launch of "T. H. Tilly" (1)

Donated by Mr. Bert Spaldin

Donated by Mr. Bert SpaldinDated 1914

Pilots and guests at the launch of the first T.H. Tilly in 1914.

More detail » MV Janica

MV Janica

Created by Francis Elsdon

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Created by Francis Elsdon

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServicePart of the Elsdon Collection collection

Dated 1987

MV Janica leaving Hartlepool. Pilot preparing to disembark.

More detail » MV Sola

MV Sola

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServicePart of the Storrow collection

MV Sola entering Hartlepool. Pilot Cutter Constantine also in the picture.

More detail » Making Smoke

Making Smoke

Donated by Mrs. Katrina Harper

Donated by Mrs. Katrina HarperA steam drifter making her way out to sea, the smoke from her funnel partly obscuring a Hartlepool Pilot Boat behind her. Former Hartlepool Pilot Bert Spaldin suggests the Pilot vessel might be the Premier, hired from January 1924 until January 1925, when the T.H. Tilly arrived from her builders in Aberdeen, the previous boat, Seaflower, having been condemned.

More detail » Meeting "H. M. S. Arrow"

Meeting "H. M. S. Arrow"

Donated by Mr. Bert Spaldin

Donated by Mr. Bert SpaldinThe Pilot Boat Crofter (built in 1975), proceeding to take a Pilot off H.M.S. Arrow.

More detail » Pilot Accidents and Losses

Pilot Accidents and Losses

Various accounts, mainly drawn from local newspapers, of accidents and incidents involving Hartlepool Pilots, including loss of life.

Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail, Wednesday, January 8th, 1879:

A PILOT DROWNED AT HARTLEPOOL. THIS MORNING. About five o'clock this morning, while John Horsley, a pilot, 47 years of age, residing in Regent-street, Hartlepool, was attempting to board the brig "Isis”, in the channel, at the entrance to the Old Harbour, fell between the ship's ladder and his small boat, and was drowned before assistance could be rendered his brother George, who accompanied him. The body was recovered about five minutes after the accident, and although the usual restorative means were applied, it was found that life was extinct. The attendance of Mr Rawlings, surgeon, was procured, hot his efforts were of no avail. An inquest is to be held.

Pilot Boat "A. G. Murrell" (1)

Pilot Boat "A. G. Murrell" (1)

Donated by Mr. Bert Spaldin

Donated by Mr. Bert SpaldinThe Pilot Boat A.G. Murrell (1), alongside the Pilot Pier.

More detail » Pilot Boat "Ebeneezer"

Pilot Boat "Ebeneezer"

Donated by Mr. Bert Spaldin

Donated by Mr. Bert SpaldinDated 1900

The small Pilot boat Ebeneezer, H3, entering the harbour under sail circa 1900. The Pilot's Pier is in the background.

More detail » Pilot Boat "Greatham" at speed

Pilot Boat "Greatham" at speed

Donated by Mr. Bert Spaldin

Donated by Mr. Bert SpaldinThe Pilot Boat Greatham travelling at speed. She arrived from her builders on October 12th, 2006.

More detail » Pilot Boat "T. H. Tilly" tied up alongside

Pilot Boat "T. H. Tilly" tied up alongside

Donated by Mr. Bert Spaldin

Donated by Mr. Bert SpaldinDated 1918

The Pilot Boat T.H. Tilly tied up alongside the Pilot Pier sometime around 1918. She caught fire and was burned-out on Sunday, 1st February, 1920.

More detail » Pilot Boats

Pilot Boats

Created by unknown

Donated by Hartlepool Museums Service

Created by unknown

Donated by Hartlepool Museums ServiceAn undated image of a number of Pilot cobles tied up at the Pilot's Pier, at old Hartlepool. In the background is the Fish Sands and the Sandwell Gate.

More detail » Pilot Cobles and the Fish Sands

Pilot Cobles and the Fish Sands

Donated by Mr. Bert Spaldin

Donated by Mr. Bert SpaldinA postcard of Pilot Cobles and the Fish Sands.

More detail » Pilot Cutter 'Crofter'

Pilot Cutter 'Crofter'

Created by Francis Elsdon

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Created by Francis Elsdon

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServicePart of the Elsdon Collection collection

Dated 1975

Pilot Cutter 'Crofter' undergoing maintenance.

More detail » Pilot Cutter A.G. Murrell

Pilot Cutter A.G. Murrell

Created by Francis Elsdon

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Created by Francis Elsdon

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServicePart of the Elsdon Collection collection

Pilot Cutter A.G. Murrell leaving Hartlepool.

More detail » Pilot coble "White Star"

Pilot coble "White Star"

Donated by Mr. Bert Spaldin

Donated by Mr. Bert SpaldinThe Pilot coble White Star, H69, in the Old Harbour.

More detail » SS Queensworth

SS Queensworth

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServicePart of the Storrow collection

SS Queensworth leaving Hartlepool with a Pilot Cutter alongside.

More detail » Seaflower

Seaflower

Created by unknown

Donated by Derek Harrison

Created by unknown

Donated by Derek HarrisonIn 1920 the Pilot boat 'T.H. Tilly' caught fire and was burnt out, being replaced by the steam fishing vessel 'Seaflower'. This vessel saw service until condemned and replaced by a second 'T.H. Tilly', in 1925.

More detail » Steamship Grano entering the Tees (1)

Steamship Grano entering the Tees (1)

Donated by Mr. Stan Lithgo

Donated by Mr. Stan LithgoA view of the steamship Grano entering the Tees taken from the Pilot boat B.O. Davies.

More detail » Steamship Grano entering the Tees (2)

Steamship Grano entering the Tees (2)

Donated by Mr. Stan Lithgo

Donated by Mr. Stan LithgoA view of the steamship Grano entering the Tees taken from the Pilot boat B.O. Davies.

More detail » Steamship Grano entering the Tees (3)

Steamship Grano entering the Tees (3)

Donated by Mr. Stan Lithgo

Donated by Mr. Stan LithgoA view of the steamship Grano entering the Tees taken from the Pilot boat B.O. Davies.

More detail » T.H. Tilly and the Brabo

T.H. Tilly and the Brabo

Created by unknown

Donated by Mr. Bert Spaldin

Created by unknown

Donated by Mr. Bert SpaldinThe Belgian steamship Brabo, with a cargo of wood pulp and steel, sank in the entrance to the River Tyne on March 14th, 1942 following a collision. Salvage work was mainly carried out by the Hartlepool steam pilot cutter T. H. Tilly, with Hartlepool pilot Tom [Tommy] Harrison in command. The remains of the Brabo were not finally cleared until the late 1940s-early 1950s.

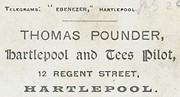

More detail » Tom Pounder - Pilot Card

Tom Pounder - Pilot Card

Donated by Mr. Bert Spaldin

Donated by Mr. Bert SpaldinTom Pounder's Pilot Card from the mid-1800s.

More detail » Tom Southern boards a tanker

Tom Southern boards a tanker

Donated by Mr. Bert Spaldin

Donated by Mr. Bert SpaldinDated 1956

January 1956. Pilot Tom Southern about to board the 1952-built bunkering tanker Tynedale H.

More detail » Vital maintenance

Vital maintenance

Donated by Mr. Bert Spaldin

Donated by Mr. Bert SpaldinDated 1951

Three apprentices carrying vital maintenance work on the Pilot Boat T.H. Tilly (the second of that name), under the watchful eye of Pilot Will Reed, in 1951.

More detail »